The American slave trade remains one of the most horrific periods of American history. No period of American history is ever supposed to be a fun, joyous experience to read about, but rather an intensely educational and reflective time for individuals, of any color, creed, ethnicity, or religious preference. The Atlantic/Transatlantic slave trade and the continuing American slavery system is an especially brutal time in the history of the United States.

Perhaps more consequential, divisive, and controversial than any other matter in American history is the system of slavery that was created in the 1600s, continued officially as slavery into the 1800s, and was replaced by Jim Crow laws during Reconstruction and up into the present day, where many Jim Crow laws live on today in various forms, most seriously in voting laws.

Many in the United States, both young and old alike, classify the Atlantic Slave Trade, the American slavery system, and the Jim Crow laws as reprehensible acts, crimes committed by White Americans and English, and a stain upon the United States. They are clearly correct, but many would halt or waver at classifying these incidents and historical acts as genocide. Yet, these events should be classified as genocide given they meet the legal criteria for such crimes and also follow a very similar line when looking at other, more internationally recognized forms of genocide.

From the Slave Trade to Jim Crow

Slavery has been around in the United States since before the first Africans arrived in the New World. The first enslaved Blacks in the New World were brought by the Spanish, not the English; when the Spanish first settled in St. Augustine, Florida in 1565, they brought with them enslaved Africans.

In 1619, according to a letter written by Jamestown settler John Rolfe some 20 enslaved Africans were “brought by a Dutch ship to the nascent British colonies, arriving at what is now Fort Hampton, then Point Comfort, in Virginia”. Due to the importance of enslaved Africans in manual, physical labor throughout the New World, for the development of cash crops like tobacco and cotton, slavery effectively became one of the main ways in which American wealth and status increased in the world.

Edward E. Baptist, a professor of history at Cornell University and scholar on the economic system that was U.S. slavery, detailed in an interview with Vox, “One of the myths is that slavery was not fuel for the growth of the American economy, that it actually the brakes put on US growth … And yet that period is when you see the US go from being a colonial, primarily agricultural economy to being the second biggest industrial power in the world — and well on its way to becoming the largest industrial power in the world”. According to Baptist, with the enslavement of Africans being a national phenomenon, the economy sped up remarkably and completely transformed the United States from an economic perspective.

With this economic growth, however, came instances of barbaric and intolerable actions perpetrated upon Africans and their descendants. In 1805, a Quaker printer named Samuel Wood published a broadside, a “single sheets of paper printed on one side only … chiefly textual rather than pictorial [which] served as a vehicle for political agitation” intending to galvanize people and refocus their efforts on the issue of slavery and towards abolition.

Wood writes, “WHEN[sic] a ship arrives at the port in the West-Indies, the slaves are exposed to sale, (except those who are very ill, they being left in the yard to perish by disease or hunger.) … In none of the sales, is any care taken to prevent the separation of relatives or friends; but husbands and wives, parents and children, are parted … The field slaves are called out by daylight to their work: if they are not out in time, they are flogged”.

Wood further details that there are times when slaves, due to the stresses of their situation, frequently would lose hands, legs, and arms or die while operating heavy machinery, how slaves would, at the most, survive upon “Nine pints of corn, and one pound of salt-fish a week”, how whippings and beatings were common to the point of death due to infection or disease, and how overseers and plantation owners would often drop hot wax or lead upon their slave property.

For female slaves, their plight was much the same. Expected to work at the same rate as male slaves they were “expected to put the needs of the master and his family before her own children [and] faced with the prospect of being forced into sexual relationships for the purposes of reproduction” often being subject to violent sexual assault or witnessing such actions perpetrated against their own children. In some cases, pregnant women were whipped to the point of miscarrying.

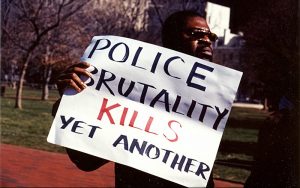

While slavery was abolished in late 1865, Jim Crow laws throughout the South reinstituted much of slavery’s basic tenets and continued into the 1960s and beyond.

Submit here

How U.S. Slavery Constitutes a Genocide

The enslavement of Africans and African-Americans in the United States is a genocide, pure and simple. There is no other way in which to classify the atrocity that it was.

First, the American slavery system of the 1600s to the 1900s shares many remarkable similarities to other incidences denoted as genocide. Take for example the most internationally renowned instance of genocide, the Jewish Holocaust from the 1930s to the 1940s committed by Nazi Germany.

The Jewish Holocaust first began with the “dehumanization and vilification” of the Jewish people, through forms of social ostracizing and demarcation through law. Property was stolen, individuals were forced out of their homes and neighborhoods to slums or ghettoes, they were denied the ability to study or pursue work, and subject to public beatings, and executions eventually culminating in the mass extermination of them as a people group. The same thing happened to Africans brought over from Africa to the United States and occurred once they were living in the U.S.

African slaves were deprived of any kind of legal process or consideration before the law (the Three-Fifths Compromise in the U.S. Constitution and the Dred Scott decision clearly exemplify this), had no real form of property or personally owned land or items (they themselves were considered the property of their white masters), they were forced to work until they would no longer be of any economic value, they were subject to rapes, beatings, and killings. The similarities between the slave experience and the experiences of pre-genocide activities in places like Rwanda, Cambodia, Nazi Germany, and elsewhere throughout the world.

Adam Jones, a professor of political science at the University of British Columbia known for his study of genocides and international relations, authored one of the most authoritative works on genocide in 2006, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. In this work, he discusses the American slave system, writing, “A reasonable estimate of the deaths caused by this institution is fifteen to twenty million people – by any standard, one of the worst holocausts in human history … To call Atlantic slavery genocide is not to claim that “every abuse or crime” is genocide … nor is it even to designate all slavery as genocidal. Rather, it seems to me an appropriate response to particular slavery institutions that inflicted “incalculable demographic and social losses” on West African societies, as well as meeting every other requirement of the UN Genocide Convention’s definition. Moreover, the killing and destruction were intentional, whatever the incentives to preserve survivors of the Atlantic passage for labor exploitation … If an institution is deliberately maintained and expanded by discernable agents, though all are well aware of the hecatombs of casualties it is inflicting on a definable human group, then why should this not qualify as genocide?”

Jones raises a very powerful question: if aware of such an action that is capable of killing numerous quantities of individuals and is predicated upon racial, ethnic, or other aspects, then that begs the question as to why this would not be considered a genocide. Another matter that Jones raises is the United Nations (UN) Genocide Convention of 1948.

In the aftermath of the Jewish Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany, the United Nations Genocide Convention of 1948 officially codified what genocide meant and determines how other nation-states can work to enforce such activities aimed at preventing genocide. Prior to this, on 11 December 1946, the United Nations had defined what genocide meant as a crime under international law, determining genocide was the denial “of the right of existence of entire human groups, as homicide is the denial of the right to live of individual human beings. Such denial of the right of existence shocks the conscience of mankind, and results in great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions represented by these human groups”. This definition was later worked into the UN Genocide Convention of 1948, which the United States only ratified in 1986.

During the crafting of such a document, U.S. officials “worried not just about being accused of genocide against Indigenous peoples but also against its Black population – an issue they knew the USSR would underscore … [insisting] on language that would minimize this possibility, including the high, intent-based threshold and focus on physical destruction”. Even legal minds who disagree with the classification of Black slavery as a genocide agree these conversations took place and they were concerned about this convention being used against them for the current actions occurring by states and federal authorities in the Jim Crow South and across the nation.

Conclusion

The American slavery system and the overall treatment of Africans is one of the worst crimes ever committed by the United States. However, even though it meets the legal criteria for a genocide and the eyewitness, documentary, and forensic evidence shows that to be the case, likely millions of Americans would shirk the mere consideration of the American slave system as a genocide.

This is partly due to the immense misunderstandings of the history of U.S. slavery and the U.S. Civil War. These myths, misconceptions, and false beliefs are pervasive and persistent in the American consciousness. Rooting this out by properly educating the youth, the future policymakers and scions of business is highly important to prevent these myths and misconceptions from taking root is key. That is likely one of the only ways in which we as a society and nation can prevent these misconceptions about the African experience in America and better teach the U.S. slave system as it is intended to be studied and explored: as a genocide.

Be First to Comment