The Trump administration has changed America for the following decades, especially regarding China. As one of the main themes of his presidential campaign, Trump has ascribed the Asian country as the great enemy of America’s economy and the main job-stealer of the working class. Even though the Obama administration has launched projects to halt Chinese advancements in foreign trade (e.g., Trans-Pacific Partnership), the Trump era has initiated harsher actions towards this goal.

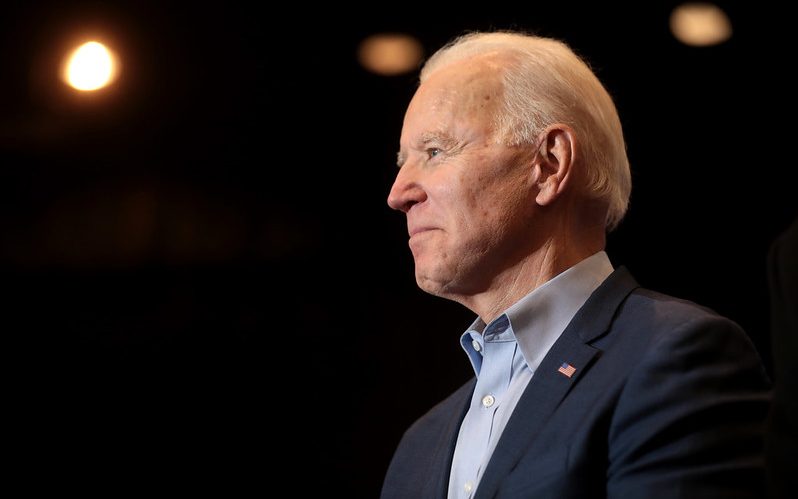

From trade war to direct insults to bureaucrats in Beijing, Trump has brought ordinary Americans’ attention toward China. However, fast-forward to Biden’s election victory and the beginning of his administration, America’s stance concerning China might have changed in its method but not in its content. Despite a more conciliatory position towards Beijing (which is America’s biggest trade partner and the second-biggest economy in the world), Biden’s foreign policy is no softer in attaining its goals to stay the number one nation and retain primacy in global affairs given that his interim strategic guidance has stated that “this agenda will strengthen our enduring advantages, and allow us to prevail in strategic competition with China or any other nation” 1. However, being tough does not necessarily mean being efficient.

One of the first major political movements of the Biden-Harris administration regarding containment of China and other US rivals (such as Russia, for example) has been the Summit for Democracy. Held virtually last year on December 9 and 10, this meeting has gathered more than a hundred leaders “from government, civil society and the private sector in our shared effort to set forth an affirmative agenda for democratic renewal and to tackle the greatest threats face by democracies today through collective action” 2. Beyond only helping democracy thrive globally, one of the Summit’s goals was to create a democratic front against the autocratic world consisting of, among others, China and Russia. However, the question guiding this article is: Will this work?

Despite some critics arguing, among other things, that some of the countries invited have recently violated democratic principles (India, Philippines and Poland, for example), the meeting is a clear sign of a world diving into a general division between democratic versus autocratic regimes. As stated by Robert Kagan: “the foreign policies of the United States and the democracies need to be attuned to the political distinctions in today’s world and recognize the role the struggle between democracy and autocracy plays in the most important strategic questions” 3.

Moreover, this idea of bringing democracies together in order to enhance America’s primacy in international politics is not necessarily new. Experts in American foreign policy such as Francis Fukuyama4, John Ikenberry5 and others have already said way before Biden’s manoeuvrings that a concert of democracies would be essential for a safer international environment.

According to these thinkers, the idea of an international organization composed only of democracies would enhance cohesion and facilitates cooperation among those nations since they share the same values both externally and internally, unlike autocracies like China, Russia and Iran. According to Ivo Daalder and James Lindsay6, international organizations such as the United Nations and its bodies “often do a remarkably effective job” when “confronted with a particular task – resettling refugees, feeding the hungry, eradicating diseases”. But in many instances, and especially in hardcore security questions, the UN falls far short. The UN must have a consensus to act, but consensus is usually difficult to achieve”. To face this problem, then, those authors argue that “the solution lies instead in organizing the world’s democratic governments in a framework of binding mutual obligations”.

However, one question arises from all these perceptions: why did this not take place earlier? Why is America trying to create something similar to the Concert of Democracies only in 2021 and not when its power was at its peak, as right after-Cold War period?

Actually, the United States has tried to implement something familiar in 2000. Under the title “Community of Democracies”, this meeting was held in Warsaw and brought “together countries ‘committed’ to democracy”, because of which it became too open, welcoming countries like Egypt, Qatar and Azerbaijan. Thus, the legitimacy of that Community was damaged by its members. Nonetheless, it is not a sufficient cause for the absence of a Concert of Democracies. As a justification for the lack of a Concert of Democracies in the past, I present two main arguments: 1) it was not necessary in the past and; 2) there were more pressing issues to deal with.

The first argument relies on what was known after the fall of the Berlin Wall as the “End of History”. With Francis Fukuyama as the founder of this idea, this thinking argues that liberal values such as democracy and free-market have defeated its main challengers (communism and nazi-fascism) and because of that, in Fukuyama’s words, “what we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” 7. Following this logic, it was not necessary to worry about any threat from Russia or China in the future, since they would eventually become democratic states contributing to a more peaceful world. There was no need for any effort to spread democracy because history would do the job.

The second point is that 9/11 happened. After the scepticism regarding the Community of Democracy due to its members, the world, especially America, watched the World Trade Center, a symbol of a new era marked by globalization and the spread of American values, being destroyed by Islamic terrorists. This started the War on Terror led by the United States and supported by countries like China and Russia. So, the whole world, and notably the great powers, were concerned with securities matters. Freedom of speech, elections and the free market would not be possible without security, making democracy promotion fall into a lower position on the list of America’s foreign policy priorities.

From this point of view, the comeback of the idea of a concert of democracies is highly connected to these two introduced arguments: the US saw that democracy would not spread as easily through the autocratic world and the threat of terrorism would not be defeated in one strike but was a long term goal involving more actions than only firepower and bullets.

However, will this new attempt work? Despite the Biden administration’s willingness to restore America’s leadership role to the levels before the Trump administration, the world has not stopped to change in the 4-years of the last American president’s governance, obligating Biden to a great amount of effort to make the country’s efforts on the international stage credible.

Now, I present four further arguments for why it is harder today than ever for this idea of a Concert of Democracy to take place and work as a front to tackle China’s and Russia’s ambitions as autocracies.

First, we need to acknowledge the current weakness of America’s global leadership. It is not the 1990’s anymore when people believed in the unipolarity of American power8, or the 2000’s, when unilateral actions from Washington received nothing more than verbal criticism. We are already living in a post-American world9. It does not mean that America is not relevant to global politics because the country still holds the biggest GDP, the biggest military force, one of the leaders of technological innovations, home of Big Tech and is to remain in this position for decades to come. The difference this time is that other major powers share the responsibility of international stability with the United States10. America is not an indispensable nation. Problems with Afghanistan, the failure in Iraq, the uncertainty to help Ukraine during a Russian invasion, let alone internal problems, are making America an unreliable partner in periods of crisis, reflecting an erosion of its ability to lead the free world alone.

Secondly, and linked to the first one, we must acknowledge the growth of China’s importance and role in international affairs. Due to the size of its economy, military and international trade, it should not be a surprise to hear that we already live in a bipolar world11. However, the significant difference between the Cold War time and today is that China is way more important economically and financially to the world than the USSR was in its whole history. The fact that the Asian country is the number one trading partner and foreign investor in a number of countries, even in traditional allies (Germany) or countries located in America’s immediate sphere of influence (Brazil) could create a resistance in democratic countries to pick sides, especially when one side is explicitly against their main trade partner. Taking America’s side could generate high costs to those countries, and history has shown that the United States will not always pay back.

The third argument is about democracy itself. The world is not as free as it was a decade ago. Freedom House states that “as a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny” 12. The increase of populist leaders in the biggest democracies in the world (Brazil, India, the UK, and America itself) has shown that even established free countries are not safe from authoritarian tendencies, which represents a mistrust in democratic values. Moreover, the great success of China’s development has attracted leaders to simulate the same in their home countries. “The Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s post-Mao pro-market reforms solidified support for the regime and made China a model for much of the rest of the world” 13.

Lastly, the world we live in today does not accept American leadership or model of government as irrefutable. Since the end of the Cold War, new and traditional powers have been taking different paths and learning how to think of a world not according to Washington’s point of view but their own. This mentality has been accentuated after the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq and the financial crisis in 2008, bringing these countries to the realization that what is good for the US is not always good for the world.

Some examples from relevant democracies regarding America’s leadership could show how complicated and unlikely of success the Summit of Democracies is. One of the latest events representing this was the AUKUS14 which, without any early warning, ditched France as Australia’s major partner in submarine construction, creating diplomatic tensions between France and the United States. Other big democracies such as Brazil and India tend to look to America’s leadership with suspicion, and their leaders have shown populists’ postures menacing democratic institutions.

This Summit of Democracies could have initiated a new era between China and the United States. With Beijing challenging Washington in many aspects, Biden is trying to enhance the greatest differences between the two nations, and he is using democratic values to do so and gather allies together. Nevertheless, China’s size and importance to other countries, including allies of the United States, the weakness of America’s leadership, and global mistrust regarding democratic regimes make everything harder for Washington. A concert of democracies could be an excellent strategy to react to China’s growing importance in international politics, but it could be too late to work.

Footnotes

- Biden Jr, J.R., 2021. Interim National Security Strategic Guidance. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT WASHINGTON DC. [>]

- The Summit for Democracy – United States Department of State [>]

- Kagan, R., 2009. The return of history and the end of dreams. Vintage. [>]

- Fukuyama, F., 2006. America at the crossroads: Democracy, power, and the neoconservative legacy. Yale University Press. [>]

- Ikenberry, G.J. and Slaughter, A.M., 2006. Forging a world of liberty under law. US National Security in the 21st Century, 17. [>]

- Daalder, I. and Lindsay, J., 2007. Democracies, of the world unite. Public Policy Research, 14(1), pp.47-58. [>]

- Fukuyama, F., 1989. The end of history?. The national interest, (16), pp.3-18. [>]

- Wohlforth, W.C., 1999. The stability of a unipolar world. International security, 24(1), pp.5-41. [>]

- Zakaria, F., 2008. The post-American world. New York, 4. [>]

- Stuenkel, O., 2017. Post-Western world: How emerging powers are remaking global order. John Wiley & Sons. [>]

- Zakaria, F., 2020. Ten lessons for a post-pandemic world. Penguin UK. [>]

- Freedom in the World 2021: Democracy under Siege | Freedom House [>]

- Brands, H. and Gaddis, J.L., 2021. The New Cold War: America, China, and the Echoes of History. Foreign Aff., 100, p.10. [>]

- Strategic agreement among USA, Australia and the UK regarding the construction of nuclear submarines for the Australian navy. [>]

Be First to Comment