We live in an era of transitional cyber politics. When I refer to this term, I do not mean simply the “hybrid war” that would have existed without the birth of audiovisual media as a given.

One interesting term is “clicktivism”, which is limited to “likes”, “sharing” and other methods of emotionally expressing Civil obligation on the internet. People involved in “clicktivism” often do not exist during street protests as individuals (unfortunately, I am one of them).

The term was actively popularized in academia by intellectual and author Evgeny Morozov in his book, “The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom (2011)”, in which Morozov discusses Colding-Jørgensen’s experiment in detail from his perspective.

The most striking example of the above-mentioned phenomenon is “Kony 2012”, a video where a Ugandan terrorist, Joseph Kony, is exposed for child trafficking.

The documentary material, created by Invisible Children Inc., aroused outrage in the public, with even the members of the US Senate becoming interested in it. However, no effective steps were taken to stop the crime and this video has also slowly surrendered to vast internet history, as did many others.

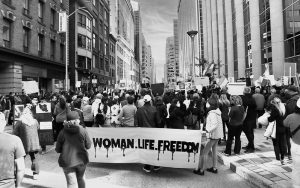

In the present, we have a reality where cyber avatars are making politics, while society is lost in solipsist cracks, obsessed with post-humanist theory and a God complex, leaving our streets to mingle with the demons of our times. In my opinion, one of the many reasons for this is the complete transformation of patriotism into a populist strategy of ideological warfare. With leaders like Viktor Orbán leading the front, the conceptual prism has become extremely narrow, leaving little to no space for a bright thought. Before we dive deeper into the fractal maze of ideological paradigms, it is important to know what ideology is and how it contributes to the evolution of human society:

Ideology in a healthy form is a system of values that exists to make our lives better, to bind us as a society, and so on. Ideology is not an axiom, as it is transformed with time and man. A very clear example of this is, first of all, precisely the very popular value system in my homeland of Georgia – libertarianism, which emerged in the bosom of the left when the famous French left-wing poet, Joseph Déjacque, called himself a “libertarian” in a publicist letter written in 1857. In his letter, Déjacque criticized a well-known public figure, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in the aspect of his sexist views on women and for his support of a market economy.

Therefore, ideology is not an absolute truth, and it is dangerous to blindly love either the right or the left. However, the popular notion in today’s intellectual circles that the left is harmful is in fact incorrect: the left has created the Suffragette movement, Stonewall uprising, Jamaican Christmas coup and many other, historically significant revolutions. The fact that you are relatively free as a woman today is a great merit of the left.

That said, a lot of advantages can be found on the right as well: for example, modern Japan has been formed by right-wing Democrats since 1955, and the revival of the country from the ashes of World War II is, in fact, their achievement. Our ideological compass also significantly depends on how we perceive human nature in an ideological context. Going back to the beginnings of the social sciences, Kant singled out two schools: humanism and realism. Humanism considers man as a wise being and categorically opposes the regulation of his desires by the state principle, while realism paints humanity as a union of destructive individuals, whose legitimate development requires the introduction of leverage at some level. The history of ideas has shown us that as a result of the selfless labor and uninterrupted change of thinkers, both thought vectors have a right to exist, the best example of which is the dilemma of Thomas Robert Malthus’s theory: Scottish economist suggests that mass production of food cannot withstand the growth of the human population, which will lead to many diseases, famine and other disasters, so the population regulates the above-mentioned potential disasters and often “controls” them with existential threats such as war. Personally, I do not agree with this way of thought, simply because I view it as completely devoid of feelings.

In general, great thinkers often claim to have guessed the historical regularity of human development and mainly base their theories on “axioms”. Clear examples of this are Francis Fukuyama and even Karl Marx himself, although many people will disagree and will bring up historical or general facts as an argument.

The 21st century is the time of revolution during the evolution, but where will it take us? This is the greatest challenge of modern society.

“Third Way” politics: a new era?

In politics, the third way is very similar to centrism, but it is different in the way that it is trying to advocate for a synthesis of centre-right and centre-left and is very akin to the new form of socialism, all while going against the traditional Marxist notion of overthrowing capitalism. It was defined very well by Tony Blair: According to him, the third way signifies the politics and ideology beyond economic determinism, with social justice becoming the core. Aside from the fundamental one, there are many more definitions in the modern-day that can be used to ontologically describe the idea: Anthony Giddens, a prominent sociologist, described third-way politics as “the new order” type of alternative neoliberalism and social democracy in the era of globalization. In a sense, the third way can be associated with a new distinguishing policy program that rearranges the way we view economics and social justice, which might end in the centre-left wing dominating the current rule of the neoliberal agenda.

The third way has been extremely prominent in British politics, especially after being widely popularized by Blair, but British pollical culture, focusing on the vastly evolving market economy, has had a hard time accepting it as a way of political thinking: for example, Peter Hand of Student Pulse writes:” The Third Way’ is not so much a new ideology, but more a new tactic, whereby Mr Blairs’ ego can be accommodated somewhat, with him thinking that he does indeed have a ‘vision’. For in reality, Mr Blair has only ever focused on one thing, the attainment of power – power at any price.”

Personally, I view the 21st century as the era of deconstruction of the history of modern ideas, so any new ideologies can prove to be vital for human evolution.

While ontology has shown itself to be capable of swift metamorphosis, we still need a point in time where we will be able to apply it successfully to our way of living, which, in the case of the third way, creates a dilemma for me: why cannot virtue ethics be expressed through a developed set of ideas?

In the aforementioned article, Bill Clinton, 42nd president of the USA, is widely cited as the progenitor of the third way of political thinking in the American culture, but Clinton’s main ideological alignment lay with pacifism, the set of values that Obama and currently, Joe Biden have inherited, which have actively shifted the power centre in world politics: America, as the “defender” of the democratic agenda, has plunged the world into lost and obscure ideological labyrinths: while recognizing critical race theory and challenging domestic political discourse, it has completely betrayed the third world, with Joe Biden being anything but a threat to Putin’s regime and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortes taking it to Twitter at the start of Russia-Ukraine war, that US intervention in the Ukraine conflict would be tantamount to another manifestation of post-colonialism. That is when the crisis kicks in: Does America, the capital of cosmopolitan society, abide by the idea of being a cosmopolitan patriot?

“Patriotism, just like life and the connections with it, is present within one when they are born into this world; it contains pieces within itself that a no sane human can deny and those so-called pieces show themselves in mother language, historical past, historical territories, in the faces of famous figures, literature and so on. The moment a child is brought into this realm, aside from inhaling, having a bed to sleep on, it needs a caregiver and milk to exist, a lullaby to remain calm.”

Vazha-Pshavela, “Cosmopolitanism and Patriotism”, 1905

Vazha-Pshavela, a prominent Georgian thinker, was way ahead pioneer of many prominent ideas in thought, though his legacy still remains unseen by the west, even to this day:

In my opinion, Vazha perfectly expressed the concept of the ideal middle ground, without making a populist statement:

“While the current conflict might not be directly linked to Vazha, the ideas expressed in his work, are: having written his essay “Cosmopolitanism and Patriotism” during the year 1905, the year of the Russian revolution, Georgia under its rule was facing a lot existential dilemma. Vazha, being at the frontlines of intellectual liberation, was always an advocate of international ideological integration, ontologically pioneering the idea of globalization, while also firmly believing in the concept of an individual state. According to Vazha, “all geniuses emerged from national roots and were worshipped by a single homeland until the world came in awe of their talent and accepted them as sons, therefore, intellects have found “home” that lies beyond their homeland- the humankind itself,” meaning that he believed in the unity, solidarity of other nations, while also having a strong national identity”, I write in my essay, which serves to popularize the works of the above-mentioned genius, while adding:

“Today, we, as an international society, must be both patriots and Cosmopolitans, as the threat upon us concerns both the legitimacy of individual states and the future of the free world. The choice is ours.”

Allaboutvazha (2022). Cosmopolitan patriotism during the crisis, allaboutvazha.com, https://www.allaboutvazha.com/cosmopolitan-patriotism-during-the-crisis/

Allison, Henry E. (1971). “KANT’S TRANSCENDENTAL HUMANISM.” The Monist, vol. 55, no. 2, 1971, pp. 182–207. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27902214. Accessed 6 Jun. 2022.

Joseph Déjacque, De l’être-humain mâle et femelle – Lettre à P.J. Proudhon par Joseph Déjacque

Morozov, Evgeny (2011). The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. New York, USA: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-874-1. Hardback edition.

[/expand]

Be First to Comment