Scientific truth is not perfect, not permanent, not immediate, and not necessarily the ultimate truth. Science does not deliver the ‘meaning of life’ truth – but science is always getting closer to the truth. While science is humanity’s transcending achievement, science as a way of thinking is an evolving enterprise. What makes science work? What constitutes good science? What are the boundaries of science? How deep can science dig into the foundations of the world? These are the kinds of questions that “philosophy of science” asks. However, some scientists dismiss philosophy as archaic, a hindrance to science, a nuisance to its progress.

In contrast to the claims about how philosophy is not harmonious with philosophy, philosophy has had a major impact on science and scientific inquiry. Even though anti-philosophical rhetoric is often detrimental to the pursuit of scientific discovery, empirical evidence indicated by the discovery of the Higgs – Boson particle, Einstein’s predicted gravitational waves, and the constant inability of physicists to find super-symmetry, scientists have questioned the legitimacy of the stance taken by physicists regarding anti-philosophical sentiments. In order to better understand and further improve the scientific method, this paper believes that science does indeed need philosophy as an instrument to reflect and critically evaluate its methodology.

Notable scientists and leaders in their respective fields have often argued that philosophy is damaging to science. Steven Weinberg, a Nobel Laureate in physics, stated that physics does not need philosophy to uplift itself. On the contrary, physics needs to detach itself from philosophical inquiry (Steven Weinberg, 1994). Stephen Hawking, a renowned name in the scientific community, famously regarded philosophy to be dead because he perceived that all the integral questions were asked by physicists (Hawking, 2012). Considering these rigid remarks by leading men in their respective scientific domains, it truly leads us to question ‘why does modern science needs philosophy?’. The following paragraphs of this article will elucidate the historical and contemporary significance of philosophy in establishing the modern scientific methodology and how it continues to play its role even when scientists continue to devalue the importance of philosophy.

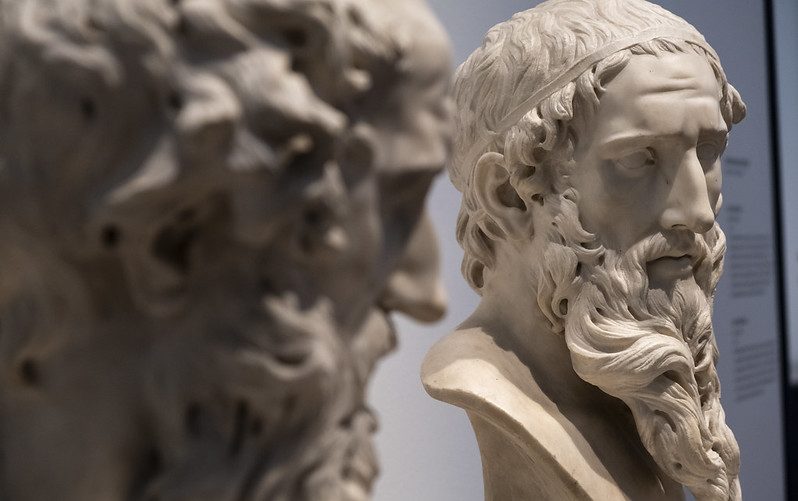

In Ancient Greece, the youth were educated in famous schools. However, the Academy established by Plato (Socrates’ pupil) and the school of Isocrates were the two most notable institutions. The two schools had a difference of opinion and approach. While Isocrates focused on achieving practical education, enabling the youth of Athens to acquire useful skills, Plato’s Academy was adamant in discussing questions about fundamental topics such as justice, morality, ethics, and beauty.

Even though Isocrates criticized Plato’s methods of educating his pupils, his arguments are in exact alignment with what Weinberg and Hawking had to say about philosophy, having no role to play in science. Isocrates stated that, ‘Those who do philosophy, who determine the proofs and the arguments … and are accustomed to enquiring, but take part in none of their practical functions, … even if they happen to be capable of handling something, they automatically do it worse, whereas those who have no knowledge of the arguments [of philosophy], if they are trained [in concrete sciences] and have correct opinions, are altogether superior for all practical purposes. Hence for sciences, philosophy is entirely useless‘ (Gruyter, 1996)

This criticism is quite illuminating if one tries to identify the similarity of how philosophy is regarded today by dogmatic men of science who are rigid in their approach to viewing scientific inquiry to be the sole approach for discovery and finding meaning.

In response to Isocrates’ criticism, Plato wrote a short response, the Protrepticus, a text which inspired a young Aristotle, who eventually became the most influential individual in the development of philosophy and the sciences for centuries to come.

The works of Aristotle and the legacy he left behind are quite indicative of his perspective, which explicitly saw philosophy as an integral constituent of scientific discovery. For instance, a direct descendent of philosophy can be sought in the understanding and exploration of everything we know about the Earth’s shape, its magnitude, the shape and size of the moon and the sun, the solar system, and the motion of the planets. All of these essential understandings are the result of philosophical thought being coupled with the scientific endeavor.

These developments were fueled by questions once asked in the Lyceum and the Academy. Hundreds of years later, notable scientists such as Newton, Copernicus, and Galileo initiated their experiments which allowed us to know about these natural phenomena. Without the philosophical intrigue showcased by Plato’s approach to asking questions, none of what we know as modern physics or science would exist today (Rovelli, 2015).

Even in the 20th century, philosophical influence continues to assist major advances in physics. For instance, Quantum mechanics is conceived on Heisenberg’s intuition. This particular revelation can be attributed to his strongly positivist philosophical surroundings in which he was accustomed to spending his time. He even states this in his 1925 paper’s abstract ‘The aim of this work is to set the basis for a theory of quantum mechanics based exclusively on relations between quantities that are in principle observable‘ (Heisenberg, 1925).

Similarly, a comparable philosophical attitude can be observed in Einstein’s discovery of special relativity. Einstein even credits his discoveries to philosophers Mach and Poincaré. He explicitly states that the conception of general relativity was heavily influenced by philosophy, and he gave credit to the philosophical arguments of Berkeley, Mach, and Leibniz (Earman & Norton, 1997)

It is clear to us that philosophical inquiry aids in the process of critical thinking and unrooting unique perspectives. However, why do philosophical tools and skills go hand in hand with what scientists need? Even though scientists are formally trained in critically analyzing and conceptually evaluating concepts. But why does philosophy become an important tool when the current scientific method scrutinizes and intricately analyses every facet of what is being studied?

Einstein answers this particular question with a specific answer, stating, ‘A knowledge of the historic and philosophical background gives that kind of independence from prejudices of his generation from which most scientists are suffering. This independence created by philosophical insight is—in my opinion—the mark of distinction between a mere artisan or specialist and a real seeker after truth‘ (Princeton, NJ, 1986)

Considering the opinions and thoughts of scientists like Schrödinger, Einstein, Heisenberg, and Bohr, we can find a plain opposition if we look at what Weinberg and Hawking previously stated. The individuals who deny the use or utility of philosophy in their process are actually exercising the process of philosophical thought. Scientists like Hawking and Weinberg have actually employed the use of philosophical thought in stating that philosophy does not belong with science or is dead. This reflection, for which philosophical thought is recognized, is actually being done by scientists who refuse philosophy to be a part of science. Thus, in declaring philosophy useless, anti-philosophical proponents are paying homage to philosophers of science.

This leads us to the question that does appreciating the “meaning of science” requires “philosophy of science”? There are two applications here. The first applies philosophy to science – exploring the nature of science and the scientific process – including the careful examination of questions and methods. Science can discern regularities, making exquisitely accurate predictions. But, can science reveal bedrock reality? The second application applies science to philosophy, addressing with science the big questions raised by philosophy. For example: What is time? – Does it flow? – What are the laws of nature? – Can they change? – How can the mind come from the brain? Will philosophy continue to wither, becoming a handmaiden of science? Or can philosophy regain its high perch as a fundamental probe of reality? The ultimate arbiter, I suspect, may be consciousness – in getting closer to the truth.

In conclusion, this article discussed the importance of philosophy in science. The question of whether science needs philosophy is an integral discussion which has constantly evolved throughout the years. While certain dogmatic positions are taken by some scientists regarding anti-philosophical sentiments in scientific inquiry, we observed how Ancient Greece initially gave birth to the idea of philosophy. Resulting in a cascading process of scientific inquiry and eventual discovery mediated by the mere ability of questioning. Thus, the basis of philosophy was established as an essential part of scientific exploration and advancement. Considering all the arguments presented, it can be stated that science does indeed need philosophy, whether or not some individuals within the scientific community deny its usefulness. One way or the other, they are employing the use of philosophy within their argumentation and rhetoric and have built on the works of scientists who have employed philosophical inquiry in their scientific discoveries and works.

Sources Earman, J., & Norton, J. D. (1997). Pittsburgh-Konstanz Series in the Philosophy and History of Science. University of Pittsburgh Press . Gruyter, d. (1996). Isocrates quoted in Iamblichus, Protrepticus VI 37.22-39.8. Hawking, S. (2012). The Grand Design. Bantam. Heisenberg, W. (1925). Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen,. Zeitschrift fur Physik 33, 879-893. Princeton, NJ. (1986). The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. Princeton University Press. Rovelli, C. (2015). Aristotle’s Physics: A Physicist’s look. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 23-40. Steven Weinberg, D. o. (1994). Dreams of a Final Theory, Chapter VII . Vintage.

Be First to Comment