China’s global prominence is not only because it is the largest provider of commodities and manufactured goods. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been equally successful in terms of politics and diplomacy, and it manages to do so by selling its authoritarian model across the globe. Whereas developing and fragile states are more vulnerable to accept it, also Western democracies have been receiving these implicit totalitarian elements. They are lured by the idea that it is acceptable to secure a win-win commercial and diplomatic cooperation with a government that adopts a political dogma which is the antithesis of democracy.

The ongoing pandemic has hit the global economy hard, and its effects have been equally witnessed in the social and public health sphere. Yet, only one country seems to have managed to avoid an economic hardship by maintaining consistent levels of GDP growth over the tumultuous past year: China, the very place the first COVID-19 cases were identified. Ever since its economic reforms in 1978, the country has maintained a notable economic performance. However, the considerable income inequality and lagging labor productivity and human capital still persist as domestic challenges. Still, on the international level, China’s numbers are sufficient to secure its place in the podium as the second-largest economy, with forecasts indicating that it will get back on track at a rate of 7.9% in 2021. Other than a supposedly effective management of the pandemic and consistent policy support, one of the factors for this rapid recovery are its resilient exports. Yet, apart from the material products that it ships abroad, there are other less obvious and immaterial elements sent abroad altogether, and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is gradually improving the way it does so. The implicit product in question is China’s authoritarian regime, and there are roughly five ways through which the CCP exports it.

Chinese Companies

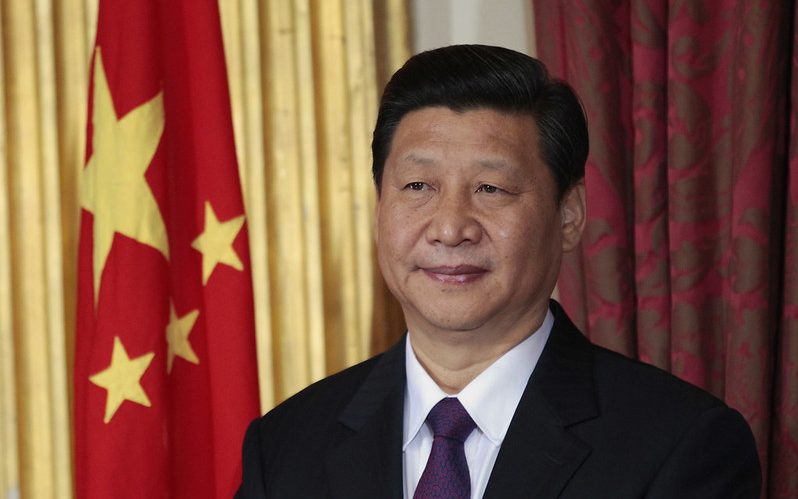

China’s political power has become much more evident since Chinese President Xi Jinping was elected in 2012, and it is not being emanated only through the political apparatus. Some of the particular ways the CCP is exerting its influence nowadays is through Chinese companies. Lately, the CCP has been establishing a greater influence on internal organizations that operate within corporations to guarantee the party’s control over China’s commercial sphere. By doing that, the autonomous status of private companies clashes with these developments pushed by the CCP since the private sector is supposed to operate independently from the reins of a government—let alone an authoritarian one. This not only compromises how Chinese companies intend to do business, but it also puts foreign companies operating on China’s soil at the risk of suffering the same kind of pressure and influence.

This practice is not unlikely to happen on a large scale according to what some past experiences involving big techs have showed us. Not even the United States private sector is immune from a potential imposition of control by the CCP. Scandals involving U.S. companies is not a new phenomenon. For instance, in February 2006 a U.S. congressional committee joint hearing produced some serious disclosures associated with Yahoo, Google, Cisco, and Microsoft, which were later accused of being accomplices to the CCP’s censorship and oppression. Another, more recent example was the controversy regarding the NBA’s submissiveness to the Chinese government’s crackdown on Hong Kong’s democratic freedom by the imposition of the national security law. Thus, it is safe to say that other private business could very well start bowing down to the CCP for profitability and secureness. By accomplishing that, it would in turn be beneficial for Xi Jinping to use companies as efficient platforms to disseminate its authoritarian model. Foreign governments should pay particular attention to corporate influence, especially because a great deal of Chinese businesses have already become dominant within the domestic market and are making big investments in foreign markets, and the CCP’s backing is one of the reasons for having enabled these companies to achieve that.

The past scandals regarding the big techs leads us to the technological and digital networking front. To begin with, China is at the bottom of the list in terms of overall freedom. According to Freedom House, the country is among the bottom twenty least free countries in the world with political rights and civil liberties scoring one of the lowest marks. When it comes to freedom on the internet, the scores follow the same pattern due to the numerous obstacles to access, restrictions on content, and violations of user rights. In 2020, the same entity published an annual comprehensive report on internet freedom and pointed out that many governments took the opportunity of the COVID-19 pandemic by using it as artifice to improve their “online surveillance and data collection, censor critical speech, and build new technological systems of social control.” So, it does not come as a surprise that China maintained its status as “the worst abuser of internet freedom” of 2020. The ongoing pandemic was—and has been—the perfect instrument for the CCP to consolidate the digital authoritarianism they had so long desired.

Huawei

Although it has somewhat limited the expansion of its private enterprises abroad, the same is not true for big techs like Huawei, a company that poses a significant strategic interest to Xi Jinping. Huawei has been accused of being used as a tool of cyberespionage and sabotage with a high potential of compromising telecommunication networks, a claim that has been originally made by the United States—more insistently by Donald J. Trump—and reproduced by its allies since then. The central issue regarding the company has to do with the provision of the fifth-generation (5G) technology, which could dramatically enhance the CCP’s capacity to create a “digital iron curtain.” Whereas the exchange of accusations particularly regards the U.S. due to concerns related to intellectual property theft, other countries—especially those in Latin America, which already have Huawei’s older technological equipment set up for their domestic networks—would not be immune from this same kind of conduct. Rather, the consequences could be even more drastic because of the general lack of cybersecurity measures in countries like Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico.

The dependency of Latin American countries on a cheaper technological apparatus makes them an easy target for a company whose 5G networks would “essentially control the communications, infrastructure, and sensitive technology of the region’s government, citizens, and business.” However, not only developing countries opt for cheaper technology: Also Europe still does, though lawmakers and mobile operators have been showing a willingness to decrease the continent’s dependency on Huawei and create more space for regional companies such as Nokia and Ericson. Since Huawei is both a prominent player on the global stage and a strategical platform for an authoritarian government with a growing international prominence, the company could very well exchange data for the benefits of becoming the CCP’s protected tech monopoly. However, the potential dominance of networks is just one of the problems posed by big techs influenced or owned by the CCP. Similarly, violation of privacy and freedom would be witnessed abroad, too, as the Chinese mass surveillance system appeals to other authoritarian governments and, even if not adopted by others, it could still find its way through vulnerable online networks and users.

The Belt and Road Initiative

The CCP has an effective way of exporting its authoritarian regime also by means of infrastructure and development projects, and there is no better example than the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since 2013, it has been Xi Jinping’s primary foreign policy framework, often by commissioning state-owned companies to implement overseas projects. They are especially successful in states that lack basic infrastructure and have low financial capacity, which is the case of the more than 60 countries (which represents approximately two-thirds of the world’s population) involved in the initiative—some of the top countries receiving the foreign direct investment (FDI) from China are Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Mongolia, Myanmar, and South Africa. BRI projects are developed through low-interest loans, so they are seen as a win-win deal since government leaders wish to expand their industrial activities and improve employment opportunities. Yet, it is obvious to infer that the deal has asymmetric gains and China is the real winner. Some critics have pointed out that the BRI is a “debt trap,” and, in fact, it has been indicated that a couple of countries are under the risk of debt distress—though some of the projects have unexpectedly become more expensive in some cases, hence also giving rise to a domestic opposition.

As the CCP secures an economic lock with the country that is receiving its investments, it creates enough elbowroom to advance its geopolitical agenda, which eventually enables the Chinese government to consolidate a foothold in foreign soil. The BRI is the materialization of Xi Jinping’s ambition to turn China into a more assertive player on the international plane, enhancing the possibilities for the country to remodel international norms and institutions. Some argue that the initiative is more than a “[…] set of infrastructure projects or a strategy for geopolitical domination. It is an articulation of foreign policy that provides China with a way of offering a positive vision for deep engagement with virtually every aspect of daily life in its partner countries.” Namely, China is able to affect foreign societies not only by implementing its public policy and infrastructure projects but also by influencing their cultural spheres, the last of which leads us to the next element: Hollywood.

Hollywood

One could argue that the CCP’s influence on Hollywood is a mere form of soft-power propaganda. Nevertheless, artistic and culture media are perhaps the most implicit and efficient platforms to shape one’s notion on a particular subject, which in this case is China and the CCP. First, filmmakers in Hollywood have to welcome and accept modifications to their content. By the time that the CCP censorship officials convince—more like urge—them to make those “adaptations,” that in turn means that a film is also a by-product of a totalitarian mind, regardless of the extent to which it was altered and where it was produced. This practice shows that China’s official censorship tentacles are reaching communities that are not directly affected by the suppression of freedom on a daily basis. Nonetheless, as the audiences consume these modified cultural media, they unconsciously absorb hidden, implicit elements, and that is precisely what totalitarian leaders aim at as they implement their censoring measures: to portray something as though it followed a natural chain of events and line of reasoning without questioning or even perceiving it. Strangely but obviously enough—given that Hollywood gets substantial economic benefits by refraining from resistance— the shaping of mainstream movies could be described as very hypocritical since filmmakers are openly inclined to criticize the U.S. government thorough their media while conforming with what the Chinese government dictates.

International Organisations, Institutions and Agreements

Finally, the CCP is pushing its authoritarian agenda through international organizations, institutions, and agreements. It seeks to do so while also adopting rhetoric loaded with clichéd—and false—remarks such as the recent ones made during a UN Human Rights Council online session in which one official claimed that “China provides freedom of speech, publication & demonstration. Personal freedoms aren’t violated.” Because of its economic and political power, China has assumed a more important role in international fora over the last years. However, like a scholar has recently put it, one of the problems is that the Chinese government still employs a “[…] rhetoric of the global leadership to cover its attempts to advance its own interests […]” and is also reluctant to “[…] align and in some cases subordinate China’s narrow interests to the greater global good and forge a multilateral response to the global challenge.” As this inflexible position engenders a persistent disparity between discourse and actions, it becomes evident that, arguably, the CCP’s behavior in the international community is performed through mechanisms that are inherently attached to its authoritarian nature. Because of the amount of power and influence China has over the main international agencies, few government and organization officials engage in rebutting or questioning statements and actions produced by its leaders. As a consequence, the Chinese government is successful in assimilating foreign representatives into a rhetoric disguised as a democratic one.

Yet these acts do not happen only at international fora. The same type of approach is noticeable in bilateral and multilateral agreements worldwide. Two ambitious accords with the latest developments are the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Particular attention should be given to the former, especially because it is a deal between a bloc formed by consolidated democracies and an autocratic state. The EU-China CAI aims at establishing better conditions to ameliorate and generate investment and trade between the parties involved. In short, the governments that are party to the treaty would benefit from the liberalization of investment, while also securing their legitimate right to control and implement their domestic policies. Some of the objectives included in the initial text refer to, for instance, “[…] public morals […] privacy and data protection or the promotion and protection of cultural diversity.”

Surprisingly, some of the EU heads of state leading the negotiations of such an agreement do not seem to be reluctant to make a deal with a government that commits grave violations of human rights that clash with the aforementioned goals envisioned by the CAI agreement. After all, the CCP has been systematically and arbitrarily performing abusive measures against the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, suppressing Hong Kong’s freedoms by imposing a national security law to charge pro-democracy politicians and activists and covering up the brazen racism treatments against black people in China. Some EU officials argue that CAI would set their economic bloc in a more powerful position towards the United States, but this interpretation is questionable and potentially misleading. In any case, whether the CCP is deluding democracies with its carrot-and-stick economic approach or the EU is purely hypocritical, either is perhaps too early to speculate.

Conclusion

China’s dominance on the international panorama is due in no less part to its economic model. Concomitantly to that, though, the Chinese Communist Party is just as successful in taking the opportunity to include its underlying totalitarian principles in the same package. As elaborated above, it is still unsure whether this unilateral approach is aimed at covering authoritarian elements of their regime. Similarly, it is not certain that many recipient states’ leaders are turning a blind eye and deaf ear to the CCP’s aggressive position and opposing form of government. From an optimist standpoint, it could be argued that all states are showing willingness to cooperate regardless of contrasting ideologies rather than engaging in hardball tactics. On the other hand, from a gloomy view, both situations could be taking place as government officials make decisions and take actions with the intent of safeguarding the economy and society at any cost. Hopefully, the latter situation is not the one currently occurring. Otherwise, it would be imperative to urge the world by reminding what the outcomes were in the past when priority was not given to human rights and democracy.

Sources

Center for Strategic and International Studies (2021) The New Challenge of Communist Corporate Governance, accessed 23 February 2021

Center for Global Development (CGD) (2018) Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective, accessed 2 March 2021

Center for Global Development (CGD) (2020) China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative, accessed 2 March 2021

Center for Global Development (CGD) (2021), Hong Kong’s Freedoms: What China Promised and How It’s Cracking Down, accessed 4 March 2021

Center for Global Development (CGD) (2019), Belt and Road Tracker, accessed 2 March 2021

Center for Global Development (CGD) (2020) Huawei: China’s Controversial Tech Giant, accessed 26 February 2021

European Commission (2021) EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI): list of sections, accessed 3 March 2021

Foreign Affairs (2018) China’s New Revolution, accessed 2 March 2021

Foreign Affairs (2020) Freedom in the World 2020 – China, accessed 24 February 2021

Foreign Affairs (2020) Freedom on the Net 2020 – China, accessed 24 February 2021

Foreign Affairs (2020) Freedom on the Net 2020 – The Pandemic’s Digital Shadow, accessed 25 February 2021

Foreign Affairs (2020) Report: Amid Global Decline, China Remains World’s Worst Abuser of Internet Freedom in 2020, accessed 25 February 2021

Human Rights Watch (2021), Mass Surveillance in China, accessed 2 March 2021

Institut Montaigne (2021), Wins and Losses in the EU-China Investment Agreement (CAI), accessed 4 March 2021

Institut Montaigne (2019) Europe and 5G: the Huawei Case Part 2, accessed 1 March 2021

Journal of Contemporary China (2020), Rhetoric and Reality of China’s Global Leadership in the Context of COVID-19: Implications for the US-led World Order and Liberal Globalization, accessed 3 March 2021

Pen America (2020) Made in Hollywood, Censored by Beijing, accessed 3 March 2021

Politico (2021) After Huawei, Europe’s telcos want ‘open’ 5G networks, accessed 1 March 2021

Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) (2021) Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – About, accessed 4 March 2021

Swedish Institute of International Affairs (2020) What to Make of the Huawei Debate? 5G Network Security and Technology Dependency in Europe, accessed 1 March 2021

The Diplomat (2020), Racism is Alive and Well in China, accessed 4 March 2021

The Heritage Foundation (2021) Latin American Countries Must Not Allow Huawei to Develop Their 5G Networks, accessed 26 February 2021

The World Bank (2021) The World Bank in China – Overview, accessed 22 February 2021

The World Bank (2021) GPD (current US$) – China, accessed 22 February 2021

Thunderbird – International Business Review (2021) China’s emerging businesses: The next generation of global corporations? accessed 24 February 2021

UN Watch (2021) China at UN Human Rights Council [Twitter post], accessed 3 March 2021

University of California Press (2021), The Many Faces of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, accessed 2 March 2021

U.S. Government – Committee on International Relations, House of Representatives (2006) The Internet in China: a Tool for Freedom or Suppression?, accessed 23 February 2021

VOA News (2020) NBA Halts Personalizing of Apparel Following ‘FreeHongKong’ Controversy, accessed 23 February 2021

World Bank Group (2020) From Recovery to Rebalancing – China’s Economy in 2021, accessed 22 February 2021

Very good article! The author display a good view of the interests of the CCP and the dangers of its politicas/economical policys.

Very good this article. A comprehensive and clear description of the increasing China´s influence on Western democracies.