Environmental terrorism and eco-terrorism: Definitions

That our world is experiencing an increase in terrorist attacks is not a surprise. A quick look at the Global Terrorism Index 2022 report and its main conclusions is enough to comprehend the seriousness of this plague. Based on painstaking research on 163 countries, the report concludes1 that the increase in terrorist attacks and related deaths is due mainly to traditional, cyber, and religious terrorism. Geographically, the report points to the Sahel and sub-Saharan Africa as the main hotbeds where major terrorist organizations are operative, as well as Ukraine due to the ongoing war.

The present analysis will deviate from the general trend and focus on another form of terrorism likewise widespread and likewise lethal: environmental terrorism. The presence of natural resources and infrastructures, especially water-related ones, in contested areas subjected to traditional forms of terrorism, requires further attention within terrorism-related research. Control over strategic natural resources is a powerful leverage for controlling entire populations, their health and economies, which emphasizes the important nexus between environmental terrorism and human rights. Despite the widespread focus on traditional forms of terrorism, the concept of environmental terrorism is not new.

Already in 1983, Richard Ullman, Professor of International Affairs at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, stated clearly that a definition of security based merely on military terms does not convey a clear image of what reality is2. Accordingly, he defined security as “an action or sequence of events that… threatens drastically and over a relatively brief span of time to degrade the quality of life for the inhabitants of a state”3. A clearer reference to the environment was made in 1987 by the Bruntland Commission whose report drew attention to the “growing impacts of environmental stress – locally, nationally, regionally, and globally”4. Focus on the environment could relate either to the struggle to access certain resources or to the consequence of the degradation thereof. Stephan Libiszewski well elucidates the difference. In his 1992 paper “What is Environmental Conflict?”, he underscores the distinction between geopolitical and environmental scarcity. While the former results from the uneven distribution of natural resources, the latter is a form of scarcity directly related to environmental degradation. Environmental degradation, according to the scholar, is a human-made environmental change with a strong impact on human society that can lead to scarcity of a given environmental source. Libiszewski considers human-generated scarcity as the main cause of environmental conflict. A telling example is the overuse of a resource and the massive generation of pollution. All causes related to socioeconomic, geopolitical, and physical scarcity cannot be defined as environmental but resource-distribution-related conflicts5.

In 2006, Peter Gleick, an American scientist working on environmental issues, affirmed that environmental terrorism “should exclusively refer to the unlawful use of force against environmental resources or systems with the intent to harm individuals or deprive populations of environmental benefit(s) in the name of a political or social objective”6. The definition echoes the general one on terrorism adopted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). But Peter Gleick goes further and underlines the difference between environmental terrorism and eco-terrorism, two definitions often used interchangeably. He defines eco-terrorism as “the unlawful use of force against people and property with the intent of saving the environment from further human encroachment and destruction3”. Nevertheless, in certain cases, it is not always possible to define clearly the two phenomena as they often overlap. The reason is that water terrorism, as one of the main forms of environmental terrorism, lends itself to both direct and indirect attacks. The first case involves a clear targeting of water infrastructures like dams and reservoirs with an immediate impact on local people’s lives. In the second case, water is mainly contaminated by toxic contaminants that will impact people’s health in the long run. The second form is easy to apply everyone can publicly access water sources and infrastructures from many places7. While all these premises are useful for understanding the nature of environmental conflicts, they also make clear how difficult it is to define in practice whether we are in front of an environmental conflict, eco-terrorism, or a conflict moved by non-environmental hidden goals.

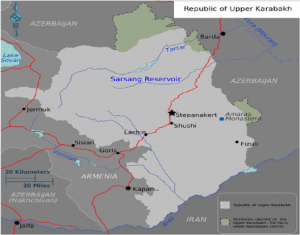

The case of the Nagorno-Karabakh wars, which interested the two South Caucasian countries of Armenia and Azerbaijan, reflects this environmental-related terminology complexity. The contested region, de jure Azerbaijani territory and de facto independent and heavily Armenian populated, at least before the 2020 war, is an interesting case. When it comes to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, most of the studies tended to interpret it through the lens of ethnic and territorial confrontation. The parties involved often put the water problem on the back burner whereas they should have handled it as one of the main points of contention since the main water resources are common to both countries. This is paramount because shared resources constitute a major problem for Azerbaijan in its capacity as a downstream country. The lack of a common framework and the almost perennial state of war makes water if not the most important issue in the region at least one to be considered as the main casus belli for future developments. Moreover, in the present case, both definitions of environmental and eco-terrorism overlap as it is often difficult to determine the actual actors involved.

The present analysis, after providing a summary of past developments in the region and the overall water situation and main infrastructures, will examine water issues’ implications after the 2020 war and the dangers involved for the future of the region. The latest events acquire additional importance since after the 2020 conflict the region witnessed serious issues concerning access to water for both drinking and irrigation. This is a problem that could potentially contribute to the perpetuation of the stalemate between the parties involved by turning the precious resource once again into the main leverage for political and economic control in the region.

The water situation in the Caucasus

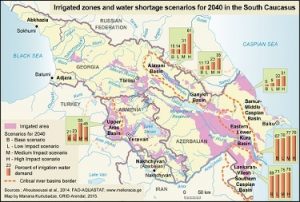

As mentioned earlier, the main issue for the three South Caucasian countries (Georgia included) is the common water resources. The three countries share the Kura-Aras River basin (Figure 1), which is generated in Turkey, and its several tributaries. The overall river basin area amounts to 190,110 km2 of which 31,5% is in Azerbaijan (downstream country), 18,5% in Georgia, and 15,7% in Armenia (upstream countries). The rest is shared between Turkey and Iran8. These water sources are mainly used for agriculture in Georgia, for industry in Armenia, and as a primary source of drinking water in Azerbaijan. The peculiar water distribution pattern reveals already the central problem: as a downstream country, Azerbaijan is dependent upon the correct use of water by its upstream neighbors, which is not always the case. Armenia, for instance, employs water resources for heavy industries. Heavy metal extraction and mining produce contaminants regularly discharged in the Aras and Kura rivers and their tributaries that ultimately reach the Caspian Sea. The same applies to pesticides, fertilizers, and wastewater because of agricultural activities upstream. The presence of water treatment infrastructures in the area notwithstanding, these date to Soviet times and are obsolete9. Another issue concerns the great number of dams and reservoirs that directly affect the Kura and Aras rivers’ flow. The result is less water flowing to Azerbaijan as upstream countries often regulate the rivers’ flow to prevent flooding that would damage crops3.

The obsolete Soviet-era infrastructures, a considerable number of dams and reservoirs scattered throughout the territory, point to another issue, namely water management legal attunement among the interested parties. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, issues related to the management of transboundary water were virtually absent as the central government directly regulated them. Nevertheless, there existed some bilateral agreements that included Turkey for the management of water in the Kura-Aras basin. Ad hoc joint commissions set up on a bilateral basis sustained the collaboration. Currently, however, there is no common platform that can address the Aras-Kura basin as a whole to offer answers to the basin’s common issues10. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the three countries found themselves with no regulations or laws whatsoever. Throughout the decades, they gradually adopted water codes and attuned them to the European Union Water Framework Directives (EU–WFD). Armenia adopted it in 1992, while Georgia and Azerbaijan in 1997. However, these codes do neither translate into concrete water control in the area nor to any fruitful attunement between the water legislations of the three countries11. Moreover, while the three countries signed the Helsinki Convention on the use and protection of transboundary waters in 1992, only Azerbaijan ratified it. Internationally, some projects were launched to support the three countries’ efforts in the water management area. The most well-known are the South Caucasus River Monitoring Project proposed by both NATO and OSCE, the EU TACIS Joint River Management Project (TACIS JRMP) in cooperation with UNDP, and the USAID’s South Caucasus Water Management Project. Unfortunately, none of these projects brought relevant results due also to the lack of substantial cooperation among them12. A good step forward toward environmental legislation harmonization was the three countries’ membership to the European Neighborhood Program in 2004 and the Eastern Partnership (EaP) in 2011. The most relevant measure was undoubtedly the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD) which set to motion the EU Water Initiative (EUWI), the main tool that provides water reform policies for the countries involved13.

Despite these good intentions, the complicated political situation between Armenia and Azerbaijan due to the contested Nagorno-Karabakh and the protracted conflict compounds any progress in the area, especially concerning water management14. The protracted stalemate unquestionably turns water resources into a precious weapon, particularly for the upstream countries in control of the major dams and reservoirs. This was the case until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. After the peace agreement signed in November 2020, by taking back several parts of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan accessed several sought-after water infrastructures. The new developments radically changed the status quo in the region and caused several fallouts for the environment.

The Sarsang Reservoir: key water infrastructure in Nagorno-Karabakh

The region of Nagorno-Karabakh is rich in water infrastructures like reservoirs and dams, the majority of which were built in the Soviet era. Considering the degree of interconnectedness among the former Soviet Union`s members, it follows that most, if not all of these infrastructures were aimed at the shared management of the region’s water resources. Of all the existing works, the most strategic one has always been the Sarsang Reservoir built on the Tartar River. This analysis chose to focus on this infrastructure due to its strategic position. Nevertheless, the territory is disseminated with dams and reservoirs that are likewise the goal of skirmishes and politicized use of water. The Sarsang Reservoir (Figure 2) was built in 1976 by the then Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan and is in a region de jure Azerbaijani but the facto under Armenian control since 1993. Its main function, besides providing the local population with drinking water was also to create an artificial basin to support irrigation. The area covered extended far beyond the conflict zone as it interested also the southeastern and northeastern areas of Azerbaijan. Annexed to the reservoir there is also a hydropower plant whose function is to provide energy to the inhabitants of both the Nagorno-Karabakh and lower Nagorno-Karabakh areas; the latter being mainly located in Azerbaijan15.

The peculiar location between two countries in a constant state of war as well as the several environmental problems that stem from it, makes the Sarsang Reservoir one of the most telling examples of the connection between war, environmental terrorism, and eco-terrorism. The Armenian government politicized the infrastructure several times to exert pressure on the Azerbaijani communities living nearby by depriving them of water both for personal use and irrigation activities. Water deprivation had and still has an undoubted impact on the health and economy of the local population and may constitute a form of environmental terrorism since a government leverages a natural resource to obtain certain results by exploiting the importance of water for irrigation activities (Figure 3). Furthermore, one of the main concerns expressed by the Azerbaijani government is the lack of proper maintenance works in the reservoir and connected dam, thus exposing local inhabitants to additional risks. Besides, after the 2020 war, there have been reactions from both sides on a local level concerning the alleged and targeted pollution of water to deliberately disrupt the economy of both communities. These accusations, prone to being interpreted as a form of eco-terrorism as per Peter Gleick, originated a social media war whereby both sides blame each other for encroaching upon each community’s right to access clean water.

Submit here

Environmental and eco-terrorism before and after the 2020 war

The 2020 war represents the tip of the iceberg of a situation ongoing since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, after which many former Soviet states redefined their borders based on ethnic criteria. Nagorno-Karabakh is one of them. After the Sovietization of both Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1920, the Nagorno-Karabakh was assigned in 1921 by the Kavburo, on Stalin’s order, to Azerbaijan, despite being populated by ethnic Armenians, and in 1923 acquired the status of an “autonomous Oblast’. In 1988, ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh demanded the assignation of the region to Armenia. The Nagorno-Karabakh war from 1992 to 1994 was the first secessionist attempt from Azerbaijan, which ended up with Armenia winning the war and occupying not only the Nagorno-Karabakh region but also some Azerbaijani territories used as a buffer zone. One of these is the Lachin Corridor, a strip of land connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. The Bishkek agreement put an end to the conflict through a Russian-brokered ceasefire. Despite many violations of the ceasefire, the situation maintained a certain stability until September 2020. The new offensive launched by Azerbaijan allowed the country to take back a great part of the lost territories, later confirmed by a new Russian-brokered ceasefire and a peace agreement signed on November 9, 2020. As of today, many skirmishes in the aftermath have been registered, and some of the points contemplated in the agreement have not been respected. Concerning water infrastructure, Azerbaijan managed to recover 30 out of the 36 dams in the claimed region. The Sarsang Reservoir, though, remains outside of Baku’s control.

Before the 2020 war, the Sarsang was at the epicenter of several recriminations. The main point raised by Azerbaijan was the reservoir’s overall condition and maintenance work. In 2015, the issue was brought to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). The latter acknowledged that poor maintenance conditions put the local Azerbaijani inhabitants at stake as it deliberately deprived them of water. Consequentially, the Assembly passed a resolution in which it stated that “the deliberate creation of an artificial environmental crisis must be regarded as ‘environmental aggression’ and seen as a hostile act by one state towards another…”, and pointed out that “the lack of regular maintenance work for over twenty years on the Sarsang Reservoir, located in one of the areas of Azerbaijan occupied by Armenia, poses a danger to the whole border region.” The Assembly, therefore, requested that “the Armenian authorities cease using water resources as tools of political influence or as an instrument of pressure benefiting only one of the parties to the conflict.”16. In 2016, the PACE´s resolution asked for a special mission made up of independent engineers to be sent to the region to control the situation. The main issue remains that the government in Baku refuses to cooperate with its counterpart in Nagorno-Karabakh, as the latter is, being de jure Azerbaijani is not internationally recognized. Consequently, the only authorities Azerbaijan is open to cooperating with are the Armenian ones, provided that the latter cease to use water as a tool for pressure and ecological terror17. Ecological terror-based accusations from both sides have become the norm after the 2020 war.

In the environmental social media-led war that ensued, the terms environmental and eco-terrorism seem to be used interchangeably by both governments. This media war was the consequence of the fact that despite Azerbaijan capturing important water infrastructures that gave the country access to the lower section of the Aras River, like the Khudafarin and Qiz Qalasi dams, the country’s water flow problems with Armenia is still a reality. Nevertheless, the main problem is that the Sarsang Reservoir is still under the control of the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities. What compounds further the situation are the upstream cotton-intensive activities as well as the earthen structure of the channels that convey water downstream. The latter is responsible for most of the water being lost on the way to Azerbaijan18. Moreover, Armenia used to release water from the Sarsang over the winter period for hydropower energy production, whereas Azerbaijan needs the water in the summer for its farming activities. Additionally, the Azerbaijani government maintains that Armenia pollutes the water deliberately, while Armenia believes that Azerbaijan, even before 1994, diverted water from the Sargsang and targeted water infrastructures on purpose during the 2020 war, an action that could lead to a major environmental disaster3.

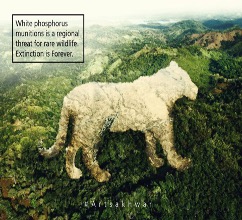

A report published in 2021 by the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOB)19 elucidates very clearly how water infrastructures were politicized and became the object of an eco-terrorist war unleashed on social media based on disinformation (pic.4). The report does not only refer to the Sarsang but also to other important infrastructures like the reservoirs Khudaferin and Sugovushan, recently taken back by the Azerbaijani army, as well as the Sarsang hydroelectric power plant. The importance of the Sugovushan reservoir lies in that it partly allows control of the Sarsang’s waters. Based on the definitions provided in the first paragraph, the several tweets analyzed in the report are a good example of both environmental and eco-terrorism. Accordingly, the tweets fire accusations not only against governments and the army but also against local people acting unlawfully against the environment to supposedly defend it from intruders and to prevent its further deterioration. Water resources in Nagorno-Karabakh and the Sarsang Reservoir were the main protagonists of the analyzed information war.

The report highlights the unprecedented importance of weaponizing the environment through social media and the spreading of fake news to increase the sense of environmental disaster as a form of terrorism. The main themes treated by private users were the cutting down of trees in the forests of Kalbajar by Armenians leaving Nagorno-Karabakh, the supposed use of white phosphorus by the Azerbaijani people in cooperation with Turkey to destroy Nagorno-Karabakh’s ecosystem, the targeting of civilian infrastructures with an impact on the environment, the intentional burning down of houses by former Armenian residents that would endanger the ecosystem of the Lachin corridor, spreading fires, and the supposed killing of several animals by former Armenian residents. Despite the variety of themes, these posts have one thing in common: the word ecocide. These “ecocide” interventions allegedly carried out by local inhabitants with the supposed aim to protect the environment, whether they are Armenians or Azerbaijanis, seem to fit into the definition of eco-terrorism. Nevertheless, the several allegations concerning the hidden hands of both governments make it prone to being interpreted as a case of environmental terrorism. A telling example was the response of the Azerbaijani Ministry of Defense to the alleged Armenian threats to the Mingachevir reservoir. Should Armenia target the reservoir, Azerbaijan would respond by targeting the Armenian nuclear plant of Metzamur. To complicate further the interchangeable use of both definitions, the report concludes that while Armenian interventions in environmental matters seem to be more civil society-based, in Azerbaijan they seem to take on an official connotation hiding state involvement. Lastly, the problem of fake news is an issue that should not be underestimated when it comes to environmental terrorism as it increases the spread of eco-related fear among people.

The confusion in the usage of one or another expression may be conscious. The recent blockade of the Lachin Corridor, the only way that connects Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, by Azerbaijani environmental activists seems to be a case in point. The temporary blockade happened on December 12, 2022, as Azerbaijani environmentalists demanded access to Aghdara to monitor Armenian mining activities and prevent the illegal exploitation of natural resources. The intervention was considered by Yerevan to be a state-organized protest based on two assumptions20. The first one is that, after the 2020 war, Azerbaijani citizens can access the areas taken back by the army only with a special government permit. The second is that, according to some open-source research, the protesters’ social media accounts seem to display a considerable number of pictures of the Aliyev family, which has been ruling the country since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The thorough research of many activists’ social media profiles highlighted that their activities have in one way or another some connection with the Council of State Support to Non-Governmental Organizations, an organ created by a presidential decree in 2021. The protests, whether or not government-led, are just the tip of the iceberg. Throughout the years, Armenia has been condemned for deliberately polluting the Aras River through the Metzamur nuclear plant and several industrial activities in Gafan and Gajaran21. The transboundary nature of water-related pollution makes it a danger also for Iran since the country shares the same water resources with Armenia and Azerbaijan. The repeated discharges of nuclear and heavy industry wastewater were a well-known fact denounced also by the German ambassador to Azerbaijan, Wolfgang Manig22. The diplomat reported as well that help was offered to the Armenian government to renew its industrial and wastewater treatment facilities. The ambassador’s intervention was deemed necessary because a German company, Cronimet, is involved in the Armenian mining sector and it is allegedly not following the required eco-standards.

Conclusion

The present review highlighted two main issues. First, the undeniable increasing importance of environmental issues in terrorist activities. Clearly, the term terrorism is used loosely, as it does not involve traditional massive attacks carried out with the support of conventional weapons but a subtle instrumentalization of natural resources, especially those with transboundary importance. For instance, in the case analyzed, the systematic discharge of nuclear and heavy industry wastewater could be considered as a chemical and biological weapon targeting downstream communities that rely exclusively on water for their livelihood. In line with what Peter Gleick pointed out23, to be effective these contaminants must be weaponized, appropriate for water dissemination, infectious, and effective over time. Another relevant point is the use of social media to spread environmental terror. These tools tend to exploit widespread ignorance and confusion about certain facts to fuel uncertainty. Ignorance stems essentially from a lack of knowledge concerning monitoring activities in certain regions, as in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh. The obsolescence of Soviet structures and uncertainty on the maintenance status of strategic structures, like the Sarsang Reservoir, contribute undoubtedly to the stalemate. The terror-related vocabulary used in digital propaganda warfare, referring in particular to environmental issues is a compounding factor, particularly when related to people’s confusion about some or all of them. Moreover, the aforementioned vocabulary tends to stress the fact that environmental degradation was human-made, which leads to what Libiszewski defined as “environmental scarcity”, which is one of the main causes of conflict.

Lastly, another problem that emerged from the present analysis is the confusion over definitions. As pointed out, the terms environmental terrorism and eco-terrorism are not the same, yet they are often used interchangeably. It is obvious that in some cases the difference is blurred, as it is difficult to define with certainty whether the government is backing citizens’ environmental protests. Nevertheless, despite the clarification suggested by some scholars, there is still a need for further elucidation on the correct use of the above-mentioned terms as they imply different actors and different goals. In this regard, enhanced cooperation on an international level can help given the looming threat of climate change as a source of environmental-related terrorism. Accordingly, a study issued by the World Bank in 2014 predicted a decrease of 52% in rainfall in Armenia by 2040, while a 77% decrease in crop production will hit Azerbaijan with a serious impact on the entire Kura-Aras basin24. In the meantime, the European Union dispatched a civilian mission to Armenia’s border areas called the European Union Mission in Armenia (EUMA) under the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP)25. As the overall goal is to create confidence and normalization in the area, the mission will hopefully make some contributions concerning the environment and water management, an issue regularly left out of negotiations. Undoubtedly a paramount intervention given the presence of water infrastructures like the Sarsang Reservoir that still constitute a real security dilemma with possible fallouts on the environment and security.

Footnotes

- Global Terrorism Index. 2023. Institute for Economics and Peace. Available at https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/ Accessed March 1, 2023. [>]

- Ullman, Richard H. 1983. Redefining security. International Security, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 129–153. P. 133. [>]

- Ibid. [>] [>] [>] [>]

- Bruntland Commission, 1987. Our common future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, World Commission on Environment and Development. In Annex to General Assembly Document A/42/427, 4 August 1987. P. 24. [>]

- Libiszewski, Stephan. 1992. What is an Environmental Conflict? Zurich: Center for Security Studies and Conflict Research. Available at https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/236/doc_238_290_en.pdf. Accessed 03-03-2023. Accessed March 4, 2023. Pp. 4-6 [>]

- Gleick, Peter H. 2006. Water and Terrorism. Pacific Institute. Available at https://pacinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2006/08/water_and_terrorism_2006.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2023. P. 484. [>]

- Ibid, p. 491 [>]

- UN Food and Agriculture Organization. 2009. Kura Araks Basin. Available at http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/basins/kuraaraks/index.stm. Accessed March 3, 2023. [>]

- Kerres, Martin. 2010. Adaptation to Climate Change in the Kura-Aras River Basin. Available at .https://iwlearn.net/resolveuid/166c61b7bbfc4def7dffa12d5102d4b3. Accessed March 2, 2023. [>]

- Halil Burak Sakal. 2020. Havza Yönetiminde Bölgesel Elektrik Ticareti Modeli: Aral ve Kura-Aras Havzaları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme, Bilig. Available at http://bilig.yesevi.edu.tr/yonetim/icerik/makaleler/3151-published.pdf Accessed April 28, 2023. [>]

- Campana, Michael, Vener, Berrin, Kekelidze, Nodar, Suleymanov, Bahruz&Saghatelyan, Armen. 2008. Science for Peace: Monitoring Water Quality and Quantity in the Kura—Araks Basin of the South Caucasus. Springer. pp 153–170. P. 162. [>]

- Ibid, p. 164 [>]

- Veliyev, Jeyhun, Manukyan, Sofya&Gvasalia, Tsira. 2019. The Environment, Human Rights, and Conflicts in the South Caucasus and Turkey։ Transboundary Water Cooperation as a Means to Conflict Transformation. Journal of Conflict Transformation, Caucasus Edition. Available at https://caucasusedition.net/the-environment-human-rights-and-conflicts-in-the-south-caucasus-and-turkey-transboundary-water-cooperation-as-a-mean-to-conflict-transformation/ Accessed March 4, 2023. [>]

- Dilaver, Tutku. 2022, ibid. [>]

- Ibid. AND Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). 2015. Inhabitants of Frontier Regions of Azerbaijan Are Deliberately Deprived of Water. Available at Https://Pace.Coe.Int/En/Files/22290/Html#_TOC_N051002C8N0510FEEC. Accessed March 5, 2023. [>]

- Suleimanova, Zulfiya. 2021. Water Security in Central Asia and Southern Caucasus. Asia-Pacific Sustainable Development Journal, Volume 27, Issue 1, p. 75 – 93. P. 86. [>]

- Veliyev, Jeyhun et al. 2019. Ibid. [>]

- Planetary Security Initiative. 2022. Water security and the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Available at https://planetarysecurityinitiative.org/index.php/news/water-security-and-nagorno-karabakh-conflict. Accessed March 3, 2023. [>]

- Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOB). 2021. Report: Investigating the environmental dimensions of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. Available at https://ceobs.org/investigating-the-environmental-dimensions-of-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict/ Accessed March 5, 2023. [>]

- Grigoryan, Ani. 2022. Who really are Azerbaijan’s ‘environmental activists’ blockading Karabakh? CIVILNET. Available at https://www.civilnet.am/en/news/686152/who-really-are-azerbaijans-environmental-activists-blockading-karabakh/ Accessed March 6, 2023. [>]

- AzerNews. 2022. Armenia commits environmental terrorism against Iran through pollution of Aras river. Available at https://www.azernews.az/nation/198053.html Accessed March 4, 2023. [>]

- Report News Agency. 2021. German ambassador: Sewage from Yerevan pollutes Araz. Available at https://report.az/en/ecology/german-ambassador-sewage-from-yerevan-pollutes-araz/ Accessed March 4, 2023. [>]

- Peter H. Gleick, ibid. p. 493 [>]

- The World Bank. 2014. Building Resilience to Climate Change in South Caucasus Agriculture. Available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/9ac1f5ec-0ea1-597f-bc23-d38145d0aa68/content Accessed March 5, 2023. [>]

- Council of the European Union. 2023. Armenia: EU establishes a civilian mission to contribute to stability in border areas. Available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/01/23/armenia-eu-sets-up-a-civilian-mission-to-ensure-security-in-conflict-affected-and-border-areas/ Accessed March 5, 2023. [>]

Be First to Comment