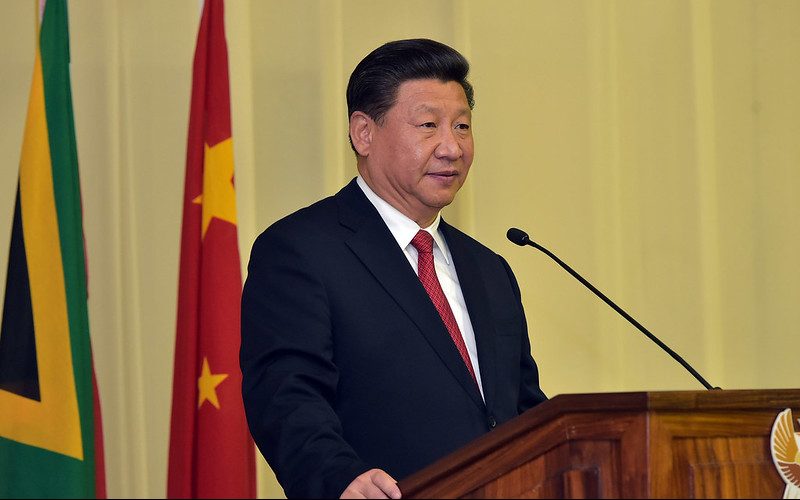

There is no doubt that technological development and political power are heavily intertwined. This has been so since the space race in the 1960s between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union. Its importance fluctuated during the cold war, but the relationship remained mainly ignored as the world reached the new millennium. However, with the rise of Trump’s protectionism and its continuation under the Biden administration, this relationship has again started to reach the front pages of many newspapers. The attention is, however, justified. Investments in research and development are one of the key factors for the competitiveness of one’s economy, and according to research, there is a positive correlation between a country’s technological innovation and its economic power (Wu, 2020). That is why it is not surprising that Xi Jinping has done everything in his power to utilise Chinese technological supremacy in international politics which is giving Beijing an upper hand in comparison to other superpowers that have yet to mobilise technological capabilities to their advantage, especially as new technologies continue to emerge.

Therefore, it is vital to examine the relationship between technological development and political power to explain how it has come to the point of China soon overtaking the US as the most powerful country in the world.

Many were surprised by Trump’s announcement of severe tariffs and restrictions against China during his presidency – the trade between China and the US has been on a steady rise during the Obama administration and there were not many direct hints that such developments could occur. However, behind the scenes, many political analysts have been carefully observing China’s rise to global power, especially after the announcement of Made in China 2025 (中国制造2025), a highly advertised industrial masterplan from 2015 that plans to turn the country into a manufacturing and technological superpower (Krishna, 2020). Commentators from both the US and China, like David Dodwell, the executive director of the Hong Kong-APEC Trade Policy Study Group, have soon argued that Trump’s acts are indeed a direct response to the programme, which focuses on 10 strategically important sectors, and has already established 5 national and 48 provincial innovation centres. Although such initiatives are nothing new in developed countries like Germany which has a similar programme called Industry 4.0 (Dodwell, 2018), what differs China from the rest is how fast and efficiently it was able to establish its technological dominance, not to mention the level of direct oversight it can exercise.

But how exactly did China reach this point? It seems that this was made possible by exercising the same approach to all its technological jewels – from Huawei to ZTE – no firms have been spared from Beijing’s influence, even if such oversight results in a loss of market share for Chinese firms on global markets. This claim is supported by Josh Bramble from the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), who writes that such an approach started in 2017 when China’s Cybersecurity Law made sure that data, which domestic technology companies have in their possession, is subject to strict regulation. This essentially prevents these companies from providing data to authorities overseas, and the Personal Information Protection Law makes sure Chinese tech companies complete a cybersecurity evaluation conducted by the 2014-established Cyberspace Administration of China (国家互联网信息办公室), headed by Xi Jinping himself (Godement et al., 2018). This has resulted in over 170-billion-dollar losses for companies like Alibaba and Didi. In the case of the latter, and many others as well, the initial public offerings (IPOs) on overseas stock exchanges were cancelled which prevented these companies from raising capital abroad (Bramble, 2021), and potentially exposing themselves to the interests of China’s competitors.

However, China’s actions are not just a response to companies trying to go global, but also to the CCP’s fear of them gaining more influence domestically, which would undermine Beijing’s power. This claim can be confirmed through the readout of Politburo’s Meeting on Economic Work for 2021 and Tsinghua University journalism Professors Shen Yang and Chen Hui’s analysis of it, in which they write that the CCP’s actions are justified because certain companies control commercial platforms and abuse their monopoly advantage (Wang, 2020). This is clear evidence that Beijing’s narrative results from their concern that companies can shape public opinion, which they have masked under the “disorderly expansion of capital” (资本无序扩张) catchphrase (Che and Goldkorn, 2021). The mentioned CCP’s December 2020 meeting could explain the Ant Group’s 37-billion-dollar IPO, also called the largest listing ever priced in history, being cancelled just a month before their sitting. Since the company is an affiliate of Alibaba, the listing event is one of the last times its charismatic founder Jack Ma was seen in public when he publicly criticized the Chinese financial industry establishment. Although he resurfaced a year later with Alibaba’s stock price severely lower because of him vanishing, his disappearance was never fully explained (Bram, 2021).

It is not just making sure that companies “unswervingly follow the Party and devote themselves to development” that the CCP does to make sure it stays at the maximum of its political power (Luong, 2021). To those companies that do follow the Party code as expected, they offer financial incentives such as R&D subsidies, venture capital financing, tax incentives, and office space, as argued by Ngor Luong and Zachary Arnold’s data brief from Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). By examining China’s AI strategy and its major group, the Artificial Intelligence Industry Alliance (AIIA) [中国人工智能产业发展联盟], the authors were able to conclude that such alliances make it much easier for the state to pick contract winners. Unlike similar organizations in the US or the EU, these alliances have the aim of strengthening the Party’s influence and the centrally planned state-driven model via the “Party building” efforts. At AIIA events, CCP officials often become incorporated into governance structures of the participating companies, making brokering deals easier. To no surprise, companies that exercise the most power within the AIIA are Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs), where the companies’ leadership is, naturally, easy to control (Luong and Arnold, 2021).

When speaking of the future technological developments both in China and abroad, it seems that the technological crackdown will continue as new technologies continue to emerge. This can already be seen with the emergence of blockchain technology which was developed to provide relative anonymity to avoid state surveillance via its decentralized nature. Since this goes against CCP’s efforts of having complete control over its financial system, there is no wonder that China has a love-hate relationship with this technology. As Alice Ekman of the EU’s Institute for Security Studies (ISS) writes, governments like China’s are investing heavily into reshaping blockchain to be compatible with their system, which was noticed by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (中华人民共和国工业和信息化部) in as early as 2016, when they stated that the technology could be considered an asset if used properly. In a way, the CCP’s has already succeeded in taking advantage of the technology by banning trading and mining of decentralized cryptocurrencies in 2021 and developing its own centralized one – the digital yuan (e-CNY), set to launch sometime in 2022 (Deutsche Bank, 2021). With its release, many fear that China will be able to increase its monitoring capabilities as the technology could be used to control transactions of political dissidents even more effectively than it is possible via the traditional financial system (Ekman, 2021).

While the West has called Beijing’s actions “technological crackdown”, the vocabulary in China is similar to that of the term “reform”, as an unnamed China analyst expressed himself in Vincent Ni’s article from the Guardian (Ni, 2021). However, one could even say that these turns of events signal a move away from China’s socialist market economy with Chinese Characteristics to Chinese technocratic authoritarianism, a similar concern to the one put forward by Tai Ming Cheung, who sees Xi Jinping as a personification of the Party which is turning the country into a national security state, resembling that of George Orwell’s 1984. This is exactly what Deng Xiaoping feared by warning of over-concentration of power in individuals, who are merely using the Party to reach their own agendas (Ming Cheung, 2020). With Xi, the era of opening up to the West when companies were invited to set up in China, and what put the country on the map where it is today – the second most powerful country in the world – has truly come to an end.

However, if China wants to become the world’s first hegemon it will need to adapt its national security policies so that companies will be allowed to achieve their full competitive advantage. As it looks now, the state has become a prisoner of its own longing for total control. Although technological development first served as a tool of the CCP to strengthen its political power, it seems that it has now turned into an act of economic self-harm. In other words, China has yet to find a balance within the control of technological innovation. Only when this is achieved will economic prosperity be certain, and China will be able to become the world’s most powerful country.

Sources Bram, B., 2021. Jack Ma was China’s most vocal billionaire. Then he vanished. Wired UK. Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/jack-ma-disappear-ant-group-ipo [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Bramble, J., 2021. Beijing’s Tech Sector Crackdown Sends a Clear Warning to Companies Going Global. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Available at: https://www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/beijings-tech-sector-crackdown-sends-clear-warning-companies-going [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Che, C. and Goldkorn, J., 2021. China’s “Big Tech crackdown”: A guide. SupChina. Available at: https://supchina.com/2021/08/02/chinas-big-tech-crackdown-a-guide/ [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Deutsche Bank. 2021. Digital yuan: what is it and how does it work? Available at: https://www.db.com/news/detail/20210714-digital-yuan-what-is-it-and-how-does-it-work [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Dodwell, D., 2018. The real target of Trump’s trade war is “Made in China 2025”. South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/business/global-economy/article/2151177/real-target-trumps-trade-war-made-china-2025 [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Ekman, A., 2021. China’s blockchain and cryptocurrency ambitions. European Union Institute for Security Studies. Available at: https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/chinas-blockchain-and-cryptocurrency-ambitions [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Godement, F., Stanzel, A., Przychodniak, M., Drinhausen, K., Knight, A. and Kania, E., 2018. The China dream goes digital: Technology in the age of Xi. European Council on Foreign Relations. Available at: https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_china_dream_digital_technology_in_the_age_of_xi/ [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Krishna, M., 2020. Chinese technonationalism: An era of “TikTok diplomacy”? Observer Research Foundation. Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/chinese-technonationalism-era-tiktok-diplomacy/ [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Luong, N. and Arnold, Z., 2021. China’s Artificial Intelligence Industry Alliance. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. Available at: https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/chinas-artificial-intelligence-industry-alliance/ [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Luong, N., 2021. Xi Jinping’s Complicated Quest for the State-Corporate Technology Complex. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2021/06/xi-jinpings-complicated-quest-for-the-state-corporate-technology-complex/ [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Ming Cheung, T., 2020. The Chinese National Security State Emerges from the Shadows to Center Stage. China Leadership Monitor. Available at: https://www.prcleader.org/cheung [Accessed 15 December 2021]. Ni, V., 2021. TechScape: Xi Jinping’s “Little Red Book” of tech regulation could lead the way. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/nov/03/techscape-china-jack-ma-regulation [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Wang, Z., 2020. Politburo meeting calls for “reinforcing anti-monopoly and prevent capital from expanding in a disorderly fashion”. Pekingnology. Available at: https://pekingnology.substack.com/p/politburo-meeting-calls-for-reinforcing [Accessed 14 December 2021]. Wu, X., 2020. Technology, power, and uncontrolled great power strategic competition between China and the United States. China International Strategy Review. 2(1), pp.99-119. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42533-020-00040-0 [Accessed 14 December 2021].

Be First to Comment