Introduction

Fairtrade International has had an enormous contribution in putting ethical consumption on the agenda, becoming an instantly recognisable label of fairness. Almost by instinct, consumers search for the little label that asserts that their purchase is giving farmers in the Global South a fair wage for their labour. However, with a growingly complicated supply chain and intensified globalisation, trade that is fair is becoming increasingly harder to ensure, despite a consumer force that is more conscious than ever (Anderson 2019). With the growing impact of greenwashing, Fairtrade is being put under scrutiny on what its role is in ensuring fair trade in developing countries, particularly in the context of growing poverty amongst farmers. Fairtrade’s initial work focused on protecting workers in the coffee sector, with coffee being the second-largest traded commodity in the world and around 25 to 30 million families depending on coffee production for their livelihoods in the Global South (Velmourougane and Bhat 2017). However, with more links developing between countries through trade, more commodities and workers have needed safeguards, leading to the certification being applied to chocolate, bananas, tea and rice, to name a few. With this growing impact, the question arises as to how relevant Fairtrade continues to be, with a focus on the coffee sector, which I will explore in this article.

About Fairtrade

Fairtrade, as a label, prides itself on its work of “[making] ethical and sustainable sourcing the norm”, contributing to the work of some of the biggest product companies such as Ben & Jerry’s and Nespresso as well as fruit and vegetable suppliers. Their work has had a crucial impact in influencing consumers’ relationship with the products they buy, an impact that has responded to risks of globalisation in the global supply chain, such as unfair wages. As Macbeth (2021) noted, 9 in 10 consumers trust the Fairtrade label.

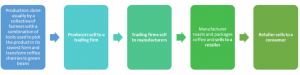

At the core, Fairtrade acts as a certification that a product has been created according to Fairtrade standards, tackling issues of poverty, forced labour (particularly involving children) and gender inequality. Their standards, which are aimed at producers and traders, vary from commodity to commodity but, in general, encompass the interdiction of forced labour and child labour, gender-based violence, and the reinforcement of the freedom of association and collective bargaining. Finally, the small-scale standard encompasses the conditions of employment, requiring wages to be set according to the Collective Bargaining Agreement.

Fairtrade offers agricultural workers minimum prices that must be paid by buyers to producers for their product to become certified under the Fairtrade standard (farmers usually work in collectives). This minimum price varies depending on many factors, but it aims to encompass the costs of production, and it ensures producers do not need to sell below the market price, which leads to Fairtrade products being more expensive. This is particularly helpful due to the volatility of coffee prices, helping alleviate this stress and ensuring a base amount for their production, regardless of the fluctuating market.

Fairtrade producers also benefit from premiums, which is an extra sum of money given to the producers and that is paid on top of the selling price of the product, allowing workers to invest this sum into projects of their choice to improve their community. This has been praised for responding to the challenges of being a small producer in the Global South and in allowing to tackle the foundation of inequalities such as education and health. According to the Fairtrade website, this has led to the development of schools, health centres and housing in poor communities as well as the development of farming techniques through machinery.

However, it can be argued that Fairtrade’s biggest impact is its role in giving a voice to farmers and reinforcing their position as key players in the coffee supply chain. This group, which used to be, and often still is, forgotten, has a platform to express their struggles and limitations through Fairtrade. This platform holds the potential of influencing policy through facts and testimonies, particularly through its partnerships with other bodies such as the International Trade Centre and the International Cocoa Initiative.

Fairtrade in practice

Fairtrade boasts plenty of benefits to its certified farmers and consumers. A study by the Natural Resources Institute at the University of Greenwich found that Fairtrade farmers were two to three times more likely to have access to training and services than non-Fairtrade farmers, receiving between 8 and 26 higher prices for their commodities (Summers, Haggar and Nelson 2017).

However, there have been downsides noted by Fairtrade. From the side of sellers, having a minimum price can make Fairtrade producers less attractive. The price volatility of coffee may cause problems for sellers as they have to maintain a price for the product they are selling while responding to the fluctuating prices of the products they are buying from producers. This also leads to the higher price tag of Fairtrade goods in the supermarket. A common issue we are seeing in this decade is the phenomenon of “label fatigue”, a lack of understanding of what each certification actually does or means due to the sheer number of labels already existing for products. Instead of customers taking the time to research what a label means, they may choose the lowest price with whatever “ethical” label is put onto the item, Fairtrade losing its appeal.

Furthermore, while Fairtrade aims to tackle the issues experienced by small-scale farmers and ensure their equality, the process of getting Fairtrade certification for producers in itself can be exclusionary and limiting. The process to become Fairtrade certified requires an overwhelming amount of paperwork and significant fees, varying from 1,300 to 4,000 USD, which can act as a significant deterrent to seeking certification. Such fees require collectives to pay each year to Fairtrade to maintain the standard of protections set out. The cost of these fees depends on the size of the cooperative, ensuring that fees can be distributed equally among collective members. However, the amount of the fees varies depending on collective size, not how much is actually produced and sold by the collective, alienating those who suffer from poor yields. As Janvry (et al. 2015) noted, Fairtrade does not guarantee the sale of a product, it is the responsibility of producers to find traders to purchase their goods, with certified farmers only selling around 22 percent of their production, making payment of fees for certification a burden.

A significant factor outside the control of Fairtrade is the climate and in particular, growing issues linked to climate change. Weather conditions are becoming more and more difficult to predict with issues such as droughts, floods and shifting pests and crop diseases destroying land and yields. Coffee prices already fluctuate massively due to the volatile nature of the climate and little protection is given to farmers who lose a yield due to climate conditions. The UN stated that droughts have the potential to be the “next pandemic” due to their frequency in the past century, having led to a loss of 124billion USD this century alone (Harvey 2021). It is a major cause of land degradation and the decline of major crops.

Those who have the tools to combat climate issues advance and poorer farmers are left behind, perpetuating the issue of inequality. It maintains the status quo of established growers, limiting room for newcomers. This holds further risks of monopolising the market as the production of certain goods, in this case, coffee, is limited to a few. This further perpetuates income inequality between countries, not only farmers, ensuring richer farming countries are able to progress and earn more compared to countries with fewer resources.

Nathan Nunn’s research exposes the positive and negative sides of the fair trade movement’s growth (Nunn 2019). Farm owners’ incomes rose as intermediaries’ profits diminish. This fulfils one of Fairtrade’s promises by helping the Southern producer. However, unskilled farm labourers remain the largest group within the trade sector (particularly with coffee) that receive no benefits from the fair trade relationship. Many crop farmers, such as coffee farmers, hire migrant workers who do not experience the long term advantages of equitable wages and FP benefits.

Is it worth it?

Research shows that the Fairtrade label does not necessarily result in higher income and lower poverty rates, in fact sometimes there is no impact as low prices are not the problem, rather productivity. Fair Trade USA conducted a study in 2017 that found that price levels of Fair Trade certified coffee was not high enough to guarantee long-term economic sustainability. This stems from three key issues:

- Farmers are largely left out of the process. Cooperatives have no market power on deciding the price of beans, so the price is not based on supply and demand. However, branded coffee can be bargained with between manufacturers and retailers.

- Fairtrade label increases the retailing price by more than farmer price premium.

However, social premiums have been found to be very helpful in permitting investment into poor communities and improving infrastructure, it also solves coordination problems in the provision of public goods. Dragusanu & Nunn (2018) found that regions in Costa Rica with higher shares of Fairtrade cooperatives have higher schooling rates.

Solutions and conclusions?

Fairtrade has had a crucial role in putting responsible consumption on the agenda. It has become known as a world-class certification of a minimum standard and is important to the world of globalised consumption today. However, many elements need to be revised. And risks of certifications need to be thought about before putting complete faith into a label on a package. How is this product certified? What are the conditions? What are the benefits? What role does corruption play?

It seems that a key problem, in my view, is that in modern days, responsibility and power are put on the consumer. Fairtrade has done things of immense magnitude to advocate for farmers’ rights but it fails on assigning the responsibility of ethics in the sector of business to the correct group. It is not the consumers who should be targeted, but rather corporations. And Fairtrade fails in working against corporations that perpetuate the very violations they fight against. Consumers should not be encouraged to buy ethically sourced goods, rather companies should be obligated to ensure ethical procedures in their supply chains. Legal obligations, that are enforceable, should be prioritised to penalise companies that do not make more of an effort to ensure everyone gets their fair piece of the pie in the supply chain. More impactful change is needed such as the development of EU standards to show more cohesive standards that are not optional in exchange for a label but are mandatory as human rights principles.

Sources Claar, V,(2016) “Is Fair Trade fair?”, Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HcUUD_PXrk&list=WL&index=3&t=12s Naegele, H., (2019) “Where does the Fairtrade money go?”, German Institute for Economic Research. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.612213.de/dp1783.pdf Subramanian, S., (2019) “Is fair trade finished?” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/jul/23/fairtrade-ethical-certification-supermarkets-sainsburys Anderson, A.M., (2019) “Do Ethics Really Matter To Today’s Consumers?”, Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2019/08/20/do-ethics-really-matter-to-todays-consumers/?sh=1a1959d02d0e Plumpton, H. and Wentworth, J., (2019) “Climate change and agriculture”, UK Parliament. https://post.parliament.uk/research-briefings/post-pn-0600/ Harvey, F., (2021) “‘The next pandemic’: drought is a hidden global crisis, UN says”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/17/the-next-pandemic-drought-is-a-hidden-global-crisis-un-says Macbeth, A., (2021) “Fair Trade: the successes and failures as seen through the sustainable development goals”, Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1191&context=honors_projects Velmourougane, K and Bhat, R., (2017) “Sustainability Challenges in the Coffee Plantation Sector”, Central Institute for Coffee Research. Summers, G., Haggar, J. and Nelson, V., (2017) “Fairtrade’s Impact on Coffee Farmers: NRI’s in-depth evaluation published”, Natural Resources Institute. https://www.nri.org/latest/news/2017/fairtrade-impacts-on-coffee-farmers-nri-s-in-depth-evaluation-published

Be First to Comment