The politicization of intelligence products is a recurring issue that can have extreme effects upon how foreign policy is conducted, how military operations and orders of battle are planned, and how intelligence is presented to policymakers.

The U.S. Naval War College describes politicization “as the shading of analysis to fit prevailing policy and politics,” while describing the politicization of intelligence as occurring “when intelligence analysis is skewed, either deliberately or inadvertently, to give policymakers the results they desire”. The College also lists a few of the ways in which intelligence is most often politicized, stating, “Intelligence analysts can be pressured to emphasize findings that support policies and preferences, or ignore issues that don’t support these policies … Policymakers clearly express what they want to hear and what they don’t want to hear [and] Estimates can be skewed for personal advancement”.

Mark Lowenthal, the former Assistant Director of Central Intelligence for Analysis and Production, expanded upon in his book Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, noting that there are positive and negative impacts, writing, “[positive politicization] arises primarily from concerns that intelligence officers may intentionally alter intelligence, which is supposed to be objective, to support the options or outcomes preferred by policymakers. These actions may stem from a number of motives: a loss of objectivity regarding the issue at hand, a preference for specific options or outcomes, an effort to be more supportive, career interests, or outright pandering. This is the more familiar case. But there can also be negative politicization where, as noted before, intelligence is provided to influence policy makers so that they change or reverse their policy”.

According to Senior Researcher Alexander Bollfrass with ETH Zurich’s Center for Security Studies, politicization can come from both above and below, meaning this can come from the actual policymakers and administrative officials as well, but also from the supporters of a political party or candidate. More often than not, historically speaking, this politicization of intelligence comes from the above, but with this current political atmosphere in which the supporters of a political party wield immense power over their party’s direction.

This politicization can clearly have an effect on intelligence and how it is presented to policymakers and the public. One of the most contested and interesting examples of the politicization of intelligence was in the lead-up to the 2003 Iraq War.

The Politicization of the Iraq War

In his book Enemies of Intelligence: Knowledge and Power in American National Security, Richard K. Betts discusses how intelligence was politicized in the Iraq War, his content being paraphrased in an article from War on the Rocks, “In one extreme case, Betts said that policymakers attempted to remove the national intelligence officer for Latin America and a State Department expert on biological weapons because their assessments on Cuba and Syria did not conform to administration views. In another case, senior administration officials released information on Iraqi weapons programs, omitting any reference to dissenting views and then prohibiting intelligence agencies from articulating dissent after the publication. A final example of politicization concerned the creation of a separate analytic effort within the Office of the Secretary of Defense to produce assessments later provided directly to White House officials without intelligence community coordination”.

Another event occurred in which Vice President Dick Cheney’s Chief of Staff Scooter Libby (later involved in the notorious Plame affair) received two papers written by the CIA’s Directorate of Analysis which documented “Iraq’s nonconnections to terrorism [and terrorist incidents like 9/11]”; Libby demanded these papers be withdrawn, yet these papers were not after both the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DDCI), the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and President Bush backed their analysts and their papers. DCI Morell later would state this “was the most blatant attempt to politicize intelligence [in thirty plus years of intelligence work]”.

Paul Pillar, the CIA’s National Intelligence Officer (NIO) for the Middle East between 2000 and 2005, also believed that much of the intelligence being utilized was politicized in some way, shape or form, writing, “official intelligence analysis was not relied on in making even the most significant national security decisions, that intelligence was misused publicly to justify decisions already made… and that the intelligence community’s own work was politicized”.

While the federal government found in a 2004 report that intelligence was not politicized during the lead-up, another investigation was held which encompassed a more broad definition of politicization (one in which there was other influence on analysts than outright pressure on them) in which the Senate Intelligence Committee did find that politicization of intelligence did occur in the sense the administration, “repeatedly presented intelligence as fact when in reality it was unsubstantiated, contradicted, or even non-existent”.

The politicization of intelligence is a very serious threat to how intelligence is collected, analyzed, disseminated, and interpreted by analysts, policymakers, and the public. As one can see with the 2003 Iraq War, intelligence was being politicized in a way beyond overt and overbearing influence upon analysts directly. This politicized intelligence (in which officials utilized intelligence that backed preconceived notions, ignored contradictory information, and intervened to a large extent on intelligence matters) effectively led the U.S. into a war that was completely based upon lies.

As one could see throughout the Trump administration, there was a large amount of politicization that occurred, perhaps more than any past presidential administration and certainly more so than the current administration. Various members of the House and Senate Intelligence Committees and intelligence professionals from the DOJ and CIA have pointed to the House Intelligence Committee’s release of the Nunes memo (a document written by Representative David Nunes which baselessly alleged an FBI conspiracy against the President) as an example of politicized intelligence and Trump’s appointment of John Ratcliffe, a two-term Texan Representative, to be the next Director of National Intelligence (DNI) who believed the Mueller investigation to be fraudulent and the entire Russia probe to be lacking in evidence, as being signs of politicized intelligence.

Political Appointees and Intelligence

To stop this politicization of intelligence, there is no clear or concrete solution. Certainly, one solution is to keep political appointees from holding key roles within the U.S. Intelligence Community, preventing purely or overtly political appointees from becoming directors of the CIA, FBI, or ODNI. Lieutenant Kevin C. McDermott of the U.S. Navy, in his 2018 thesis for the Naval Postgraduate School, writes, “Real reform must address the issue of politicization within the Intelligence Community to ensure repetitive mistakes are avoided and American service members do not continue to die in vain … The length of a term of office, when it spans greater than the length of a two term president, would reduce the likelihood that presidents would be able to exert political pressure on appointees … [implementing post-Katrina legal policy where] the DCIA and the DNI shall “have not less than five years of executive leadership and management experience, significant experience” in the intelligence community, and a “demonstrated ability to manage a substantial staff and budget”.

Many of McDermott’s recommendations are right on point. Having political appointees in sensitive positions where intelligence is collected, analyzed, and disseminated would naturally cause some, if not all, intelligence to be politicized somewhat. With the Trump administration, we have seen this at the forefront.

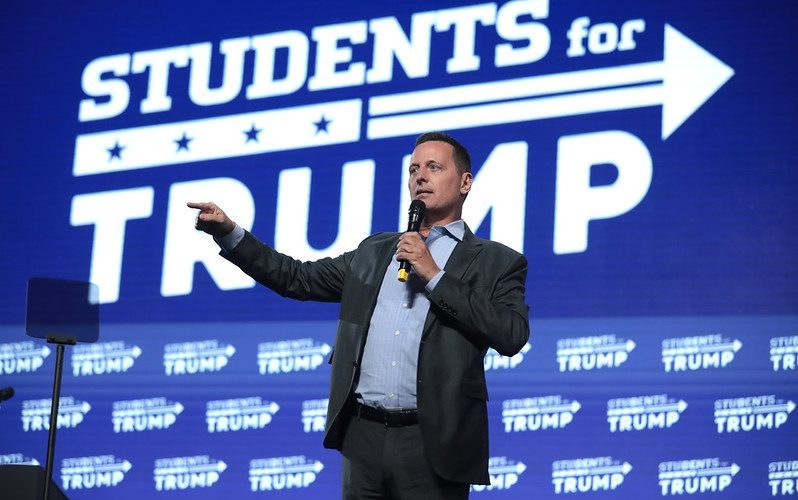

Richard Grenell, the Acting DNI for a few months in 2020, had been politically appointed to positions in the State Department and as Ambassador to Germany, but beyond that had been a political commentator and political consultant, having no previous work experience in intelligence administration or information analysis. His successor, the previously mentioned John Ratcliffe, had been the Mayor of a small town of some 7,000 persons, was a Bush appointee to be the Acting U.S. Attorney for a federal district, and had been a rather unassuming Representative for Texas’s 4th District; his experience in leading the entire U.S. Intelligence Community and being the chief advisor for the president on intelligence matters was arguably the lowest in history. Mike Pompeo as well, who held the position of CIA Director and Secretary of State under Trump, also lacked the qualifications, both personal and professional, to hold both of those posts like many, many others within the intelligence sector and government service between 2017 and 2021.

These persons exhibited no strong understanding or comprehension of how to oversee teams of intelligence analysts, covert operators or manage an entire agency that focuses on the most sensitive areas of U.S. national security.

Conclusion

Politicization can lead a country to war and can have great ramifications for all forms of a nation’s foreign and domestic policy endeavors. Politicization can result in information on foreign affairs being distorted or manipulated to better suit an individual’s, group’s, or party’s personal or political purpose, which in turn can result in resources being diverted for those unnecessary reasons and other, more pressing international developments being ignored or left to the wayside. Stopping the now common usage of unqualified political appointees being given positions in the U.S. Intelligence Community would surely be a way to stop politicization, but it is only a first step. Having policymakers who listen to the intelligence that is being collected and informed upon this by those senior leaders fluent in intelligence dissemination, considerate of geopolitical developments, and aware of how to properly provide this information to the President and other signatories who ultimately have the final say in what kind of policy and decisions are made.

Be First to Comment