The United States Southern border is perhaps one of the most contentious and controversial issues for the U.S. government and society in the current era.

This issue affects some 30 million American and Mexican citizens living on the border and increased sensitivity to the matter has only grown in the 21st century with rhetoric from the Global War on Terrorism and the 2016 U.S. Presidential election making the matter even more politicized. President Donald Trump’s immigration and total foreign policies, which were deemed extremist or even racist by some, continued the politicization and controversial nature of the matter, demonstrating how important the issue of immigration and border security is to the American populace.

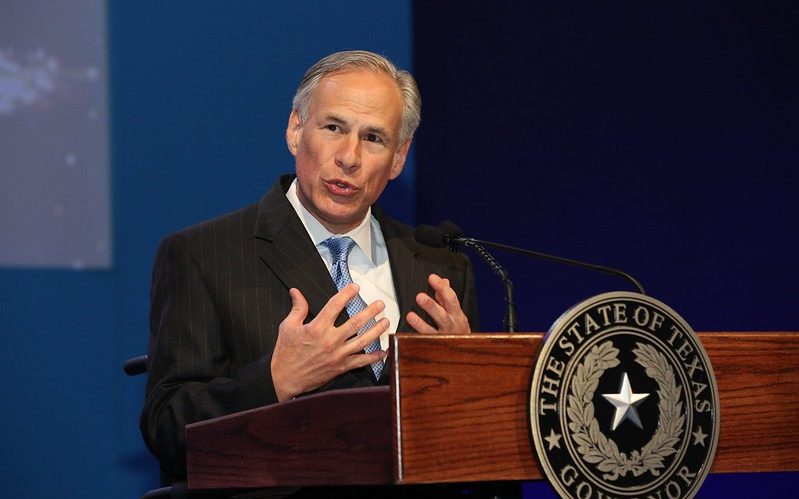

In the state of Texas, Governor Greg Abbott signed nearly 800 new pieces of legislation into law, ranging from targeting street races to banning gender-affirming care to limiting the power of district attorneys. Multiple bills also focused on border security and one of these bills, known as Senate Bill 1900, is one of the most recently controversial and impactful in terms of border security, homeland security, and immigration policy in the state of Texas.

Texas’ War on Drugs

2023 has become a defining year for the State of Texas’ war on drugs and immigration, yet this has not been a sudden development.

Historically, for nearly twenty years under the previous Republican governorships of George W. Bush and Rick Perry, the Texas Republican Party (GOP) actually “prioritized Hispanic outreach and consistently rejected polarizing immigration policies”. During the Rick Perry governorship, the Texas GOP began a steady change towards harsher, stricter immigration and border policies. This movement and shaping of the state’s policies was largely led by a smattering of Republicans influenced by Tea Party ideals with Dan Patrick and Ted Cruz, now fixtures of the Texas and national Republican parties, being quite involved.

In the respective races for Governor and Lieutenant Governor, the border was a main issue, being pushed in campaign ads by then-Republican gubernatorial candidate Greg Abbott with his overall plan having a “tough on the border/crime” theme, even though some critiqued his plan as having little in the way of funding.

With the elections of Greg Abbot as Governor and Dan Patrick as Lieutenant Governor in 2014, Texas began a sharp right-ward shift on immigration and the border, reflecting their conservative constituents’ desires. In subsequent gubernatorial elections, Texas Republicans have consistently “said that immigration or border security is the most important problem facing the state of Texas”. Reflective of the right-wing shift and acknowledging his constituents’ desires are Abbott’s numerous retributory policies, public promises and statements, and military initiatives put forth to make the border more in line with the political right’s idea of border security.

Senate Bill 1900 is but one more development in the long history of right-wing border security initiatives for the state of Texas. Building off an executive order issued by Governor Abbott in September of 2022, the bill itself, according to one of its sponsors:

“[provides] for the designation of drug cartels and other similar groups as “foreign terrorist organizations” under state law and including these organizations in the scope of certain provisions, including those regarding criminal offenses related to organized crime … [allowing] law enforcement and prosecutors to pursue higher penalties for criminal activity associated with a foreign terrorist organization [and expand] resources by adding foreign terrorist organizations to current intelligence databases and allows local entities to seek public nuisance claims against foreign terrorist organizations who are operating in their communities”.

S.B. 1900 further allows the state “to seize property owned by FTO members”.

This bill is one of many Texas bills which further increase the presence of both law enforcement and military personnel along the border. This kind of policy initiative is not an uncommon one and in fact, illuminates a frightening trend amongst more Conservative elected officials and American citizens.

At the first Republican presidential debates for the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election, outlying the Conservative party’s qualified candidates, there was little disagreement among the candidates on border security. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis stated first “I am going to send [troops] to our southern border … We have to re-establish the rule of law and we have to defend our people … We’re going to use force and we’re going to leave them stone-cold dead” with all candidates agreeing on some form of stronger security along the Southern border, the main strategy of which involved combat troops.

This kind of boots-on-the-ground, more military solution has been endorsed by individuals from all across the Republican Party, including presidential candidate Donald Trump (who attempted, but eventually gave up, on a plan to designate cartels as terrorists), Texan and Florida Representatives Dan Crenshaw and Mike Waltz respectively, and Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, all strongly advocating and encouraging a solution which would see either Special Operations Forces (SOF) or other uniformed military operators in direct combat activity with Mexican cartels. In February of 2023, twenty-one State Attorneys General (only one of whom is on the U.S. Southern border with Mexico) asked the Biden White House to, among other requests, designate drug cartels as terrorist actors. The White House’s response was a clear and staunch no.

Given this, it is incredibly important to determine whether Senate Bill 1900 would truly be effective in securing the border.

The Efficacy of Senate Bill 1900 and Other Designations of Cartel Operations as Terrorism

Designating transnational organized criminal (TOC) enterprises as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) is not a new phenomenon. With the simultaneous rhetoric from the Global War on Terrorism and the War on Drugs of the early 2000s, such an initiative has been much talked about, discussed, and researched by knowledgeable parties in the many years before this came on the radar of Conservatives. For the most part, scholars conclude that designating criminal enterprises engaging in drug trafficking as terror organizations is ineffective, though a select few seemingly advocate for such a strategy.

The Argument For a Designation

In a 2008 issue of the University of South Florida’s Journal of Strategic Security, Sylvia M. Longmire, a retired Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Special Agent with a focus on Latin America, and Lt. John P. Longmire, an active-duty Air Force officer, argue that designating drug cartels as FTOs would be quite effective.

Both make the argument that Mexican TOC enterprises “all exhibit characteristics of terrorist, insurgent, as well as criminal organizations” through assassinations, executions, and kidnappings in addition to acting like an insurgent force by countering Mexican government forces, stating that there is even a practical, historic precedent in that the United States designated the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) an FTO in spite “never having a political, religious, or ideological goal [nor] routinely engaging in violence that was not politically motivated”.

Javed Ali, a professor of the practice at the University of Michigan’s Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and a longtime counterterrorism expert with many years in U.S. government service, argued that it may be effective as it is something the U.S. has not tried before and would allow “the U.S. government to apply additional economic and financial sanctions, and also pursue material support to FTO charges that have been effective in the post-9/11 era against jihadist groups and other international terrorist threats” with the cartel’s activities fitting the definition of terrorism, such a designation being “just another tool that we just haven’t used”.

Even individuals who are against defining drug cartels as terror organizations do admit that it would provide the U.S. government with additional tactics and strategies to defeat cartels. On the surface, it does make sense to designate cartel members as terrorist actors given they meet some of the legal and practical criteria for designating them as such. However, this opens up a realm of unconsidered and unforeseen circumstances which would serve as a detriment to U.S. foreign policy and homeland security, and would politically likely come back to infuriate or trouble Republican lawmakers and legislators. Furthermore, the logic behind the designation crumbles upon a more concrete investigation into the matter.

The Legal Framework of a Designation

Looking at this problem first from a legal standpoint, under U.S. law (in particular 8 U.S. Code § 1189), designating an organization as an FTO would need to be performed by the U.S. Secretary of State; in this designation process, the Secretary would need to find that the organization in question “is a foreign organization … engages in terrorist activity … or retains the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity or terrorism” and that such action “threatens the security of United States nationals or the national security of the United States”. This criterion is what would be needed in order to legally and practically call Mexican drug cartels foreign terrorist organizations or as otherwise engaging/acting in support of terrorist goals.

Since the entire point of this is to designate something as another, the definitions are key here. 8 U.S. Code § 1189 defines terrorism as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents”.

What is difficult about this is that, while cartels do engage in acts of violence against elected officials or openly bribe or extort public officials, they do not act against these individuals to overthrow the mutually, broadly agreed upon social-political order. In fact, Mexican drug cartels “are not motivated to create a homeland to call their own, substitute their ideology for the existing one, or to achieve any other sort of political goal that is routinely associated with armed groups who instigate social upheaval” their total goal being to remove government interference from their operations and continue their overall goal of trafficking narcotics, making money.

In this sense, it would be difficult to call the Mexican drug cartels engaging in terrorism as their actions are not explicitly to remove a political threat, overthrow a government, or really obtain a political goal. Their overall motivation and desires are inherently criminal.

Some, such as the Longmires in their 2008 journal article, argue that this matter of political violence does not matter too much given their AUC case. However, what some neglect to consider with the AUC case is that, in 1997, Carlos Castaño aimed to unify like-minded groups under the AUC banner in an effort to become a legitimate political party while still engaging in violent activities and drug trafficking which included the “the kidnapping of political figures to force recognition of AUC demands … [and terrorizing and intimidating] local populations so the AUC could gain control of those areas”. Any real, legitimate discussion of the AUC case shows clearly that they were engaged in acts of overt political violence aimed at politically changing and altering the course of government in Colombia; a comparison to Mexican drug cartels indicates a lack of research or misunderstanding of the time frame.

From a prosecutorial standpoint, there would be more charges with which to apply upon individuals who are found to have engaged in drug trafficking or production.

Section 960a of Title 21 of the U.S. Code carries “twice the minimum sentence” currently being used against traffickers and “could range from 10 to 80 years” while section 2339B of Title 18 of the U.S. Code could impose a life sentence provided the statute’s criteria of knowingly providing “material support or resources to a foreign terrorist organization” are met and “resulted in a fatality”. As such, individuals and foreign nationals “acting entirely in foreign countries with little connection to the U.S.” and who are “not directly involved in drug trafficking” could become subject to these stiffer penalties. While this on the surface does sound attractive and could potentially result in charging or arresting individuals at large financial companies involved in laundering money or even political figures who assist in the drug trade, there is a greater and more likely amount of individuals who these prosecutions would harm; immigrants and migrants.

Immigrants coming from South and Central America towards the United States interact with numerous cartels along their journey upward. This ranges from migrants “offering financial support to cartels either by paying the cartels directly or by paying groups dominated and controlled by the cartels” to gain safe passage or paying ransoms to return a kidnapped family member. Under the material support charge, any migrant or family who pays a ransom or gives money to a group to get them through Mexico would become subject to this charge and be unable to claim asylum, as is common with many coming through. While one can try to legally claim duress in such a situation, the Bureau of Immigration Appeals has denied this exception and, even if allowed, the asylum seeker would have to prove the severity of duress in a court of law, this being far from easy to do and highly unlikely to succeed.

Not only this but with such a designation, it would be important to explore how prosecutions against American citizens may change. Ioan Grillo, a journalist for numerous reputable news organizations with a focus on organized crime and cartels in Latin America, wrote in a 2019 op-ed for The New York Times that Americans who engage in “straw purchases” or privately buy weapons to provide to Mexican cartels “could be charged with providing material support to a foreign terrorist organization” getting decades in prison instead of “lenient sentences with probation”. Grillo makes special note that the American gun lobby would be put in a precarious position if a “gun seller were hit with such charges”. Politically, such a designation would have unintended effects for many of the elected legislators who frequently align themselves with gun companies and the gun lobby.

Legally, however, it would appear the designation of Mexican drug cartels as an FTO fails to meet the political requirement under U.S. law. Mexican drug cartels “use violence to seek profit” not change or alter political operations and proving this would be incredibly difficult to do unless one performed a completely superficial and one-dimensional examination of the issue. From a prosecutorial standpoint, Mexican drug cartels would remain only minorly affected by the change in classification and, if anything, would serve to harm immigrants or other individuals who engage in such mundane tasks as cooking or cleaning for cartel members.

The Effects of an FTO Designation on Domestic, Foreign, and Political Policy

From a policy perspective, designating Mexican cartels as FTOs would result in a policy and perspective shift that would negatively serve to combat the flow of drugs or actual criminal activities of cartels along the Southern border.

Jeffrey Addicott, a professor of law at St. Mary’s University School of Law and retired Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army Judge Advocates General (JAG) with a record of service in support of special operations, wrote in 2012 that, if Mexican drug cartels were defined as terrorists or a terror organization by the United States, “many would immediately assume [albeit incorrectly] that the correct rule of law that the U.S. might employ would be the law of war and not domestic or international criminal law … [this] factor would put unnecessary strains on any bilateral relationship that America is building with Mexico”. While such an assumption is incorrect, one’s perception becomes their reality and the simple re-defining of Mexican drug cartels as terrorist organizations would result in a cultural shift that would negatively suit counterterror and counterdrug efforts.

Such a policy would also further increase the militarization along the U.S.-Mexican border. The elements of American law enforcement along the border, namely the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), are already a paramilitary force and pride themselves on such a term. Jason M. Blazakis and Colin P. Clarke, both academics with years of scholarly and government experience, argue that further militarization would “significantly attenuate the flow of trade and economic activity, hurting both the U.S. and Mexico … [heightening] U.S.-Mexico tensions, potentially setting back relations with an important country during a crucial time, given the ongoing border crisis”. Given how many Americans oppose the militarization of police overall, it is highly likely that further militarization would be domestically unpopular and, from a foreign policy standpoint, be seen by Mexico as an antagonistic move and either contribute to a decline or full stop to any future cross border, law enforcement policy.

Mexico has made their views on the growing call for an FTO designation on their drug cartels quite clear as well. Multiple individuals from Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs Marcelo Ebrard to the President of Mexico, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, both called the calls for armed soldiers or designation of drug cartels as FTOs irresponsible and an attack on their sovereignty.

An official, federal designation of Mexican drug cartels as FTOs would effectively destroy any goodwill remaining between the U.S. and Mexican governments. Nathan Jones, a professor of security studies at Sam Houston State University, stated in an interview that “[such a designation] would kill U.S.-Mexico relations … Are we going to treat Mexico like Pakistan, wherein we’re engaging in drone strikes? And what does that mean for sovereignty? It also would mean —and this is what would be disastrous for American policy — zero cooperation on migration issues, zero cooperation on countering narcotic issues”.

From a policy standpoint, there is reason to believe that designating and operating in a way in which the U.S. considers Mexican drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations or engage in explicitly terroristic activity would negatively impact Mexico-U.S. foreign policy, bring up unexpected and (for Conservatives) politically damaging legal conundrums, and result in little change in how the U.S. counters drug trafficking networks in Mexico.

Submit here

Conclusion

It is clear beyond a doubt that delineating Mexican drug cartels as FTOs would be legally infeasible and operationally counterproductive to annihilating the ability Mexican drug cartels have to make money, transport drugs abroad and into the U.S., or continue their own brand of violence. Calling drug cartels terrorists or wholly designating them a terror organization does not do anything to stop the violence wrecked upon Mexican citizens or the flow of narcotics into the United States. It does provide the U.S. government with some additional legal tactics to use against narcotics traffickers, yet this legal framework can also negatively impact individuals who can be highly coerced into supporting the cartels or individuals who are just as victims of the cartel’s actions as are the individuals who take fentanyl-laced drugs in the United States.

It stands to reason also that much of this rhetoric coming from Republican elected officials, presidential candidates, and the party itself is not fully about combating drug cartels, but rather again about restricting immigration and enhancing fear of the “other”. Such a designation would expand the powers of the federal government and allow larger amounts of individuals to be prosecuted and subject to charges. These individuals, under a Republican administration with a largely more conservative appointed Justice and State Department, would result in immigrants becoming targeted and further restricting any ability to claim asylum. This in turn would place greater pressure on the Mexican government to care for these individuals and any attempt to work with the Mexican government to resolve such an immigration crisis would be difficult given the U.S. had classified Mexican nationals as terrorists.

The overall policies suggested by Republican legislators and candidates is one that is incomplete, superficial, and lacking in any real consideration of U.S.-Mexico relations or effective border security. It is incredibly political and likely a ploy to be seen as tough on crime, tough on immigration, and reflective of the Republican Party’s stances on the Southern border, which plays well with the average voter, including the average American Conservative.

While this is an effort to gain votes and support for their candidacies, it should not be discarded as political manoeuvring. Given the number of individuals within the Republican Party who frequently espouse or have remained silent publicly while high-profile members give credence to extreme views, this is quite serious and would heavily affect the flow of immigrants along the Southern border and could easily harm economic, trade, and security cooperation relationships with America’s greatest neighbor to the South.

The flouting of this designation as a great solution to the flow of drugs and the threat of violence by Mexican drug cartels is erroneous. There is no single solution to the drug epidemic in the United States and, furthermore, this kind of policy would prove to be far more harmful than many would believe.

Instead, a policy of minimizing the amount of guns and weapons that flow from the United States into cartel members’ hands should be taken; increasing the security relationship between Mexico and the United States, providing funding and building on how Mexico’s government helps marginalized or disadvantaged neighborhoods and instituting an anti-corruption framework for government officials. These are less immediate and more complex solutions to the problem, yet they are backed by years of research and data and do not run the risk of putting American lives at risk, harming U.S. trade, or the delicate relationship between the United States and the United Mexican States.

Be First to Comment