Scholars have been disputing the issue of a global decline in democracy and democratic attitudes in recent years. Different theories exist on this statement, and some disagree with the topic itself. However, statistics demonstrate that something has transformed in the last decade, and it is people’s attitude toward everything political. Election participation, clarity on which party to support, and awareness about political, economic, and social problems are just a few of the shifting indicators. States are weakening, removing, or altering democratic rights, or, in certain circumstances, the political democratic order altogether. What may have caused this reversal? This pattern is frequently associated with four significant social and economic crises of the last fifteen years: the 2008 financial crisis, the refugee crisis, the Euro-zone debt crisis, and the COVID-19 outbreak and its repercussions. Although the links to these issues are arguable and need an entirely different study, scholars tend to link recession in the number of democracies to all four to varying degrees.

Democracy in crisis or crises behind democracy?

Although this article mainly focuses on more recent data, thus after COVID-19, it is essential to state that there are countries in which the health crisis appears to only have aggravated already existing sentiments of abandonment of democracy. The refugee crisis, to state one, is a prime example of a crucial issue and debate around Europe since before the pandemic, which created political tensions between countries and social issues within them. For Algan et al. (2017) it was the 2008 financial crisis that caused a surge in unemployment and consequently, the growth of populism and authoritarianism that tarnished democracy around the world. The economic crisis has eroded citizens’ confidence in national and supranational institutions (Edo et al, 2020:6). States like Poland and Hungary are the main cases in point in the debate about a rise of populist and authoritarian turns in Europe.

However, concerning the latest crisis, the pandemic, Cooper et al. (2020) outline four additional threats that arise from its outbreak. First, globalization in a nationalist form, then less democratic participation, more centralisation, surveillance state and erosion of human rights, and rising inequality (p.5). The initial concerns of “not being listened to” and distrust in public officials, both of which can jeopardise a democratic system. This is because they can lead to lower electoral participation and consequently, a lower level of participative democracy, both of which are critical to the health of a democratic state. The crises in these nations have fostered and supported undemocratic attitudes and mindsets (nativism, protectionism, Euroscepticism, authoritarianism) that reinforce each other and lead to the growth of, as Wang calls it, “populist nationalism” (Wang, 2021:31).

The impact of Covid-19 on democracy

As we specified before, the pandemic and the resulting health, political, social, and economic catastrophe have in some cases exacerbated tensions that were already undermining the political systems of some regions, while in others it has created new tensions and challenges to the political system. However, a cross-European study discovered that certain COVID-19-related measures such as lockdowns, may have had positive effects on democracy, trust in government, and support for public authorities (Bol et al. 2020). It is the so-called “rally-around-the-flag theory, which predicts a boost in government support in times of international crisis (Mueller, 1970).

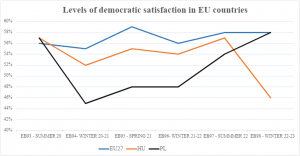

Let’s take a look at Table 1. As outlined before, the level of satisfaction in democracy can depend on several factors that differ from state to state, especially after the pandemic and the measures taken to cope with it. However, I provide the example of Poland and Hungary, which we have considered before, as well as the trend for the twenty-seven countries in the EU, to explore the levels of satisfaction of democracy in these countries and in the EU generally. The data covers the period of the pandemic and after, from Eurobarometer 93 (data from Summer 2020) to Eurobarometer 98 (Winter 2022-2023).

As shown in the graph, all three lines tend downward between Summer 2020 and Winter 2020-2021, indicating a drop in democratic satisfaction. Poland has experienced the greatest reduction, with values falling from 57% to 45% during this period. Following that, we see a continuous growth in Polish values, but a minimal fall in EU27 and Hungary values for the period between Spring 2021 and Winter 2021 -2022, dropping from 59% to 56% and from 55% to 54% respectively. Finally, while both EU27 and Poland continue to rise in their democratic satisfaction ratings, Hungary’s dips substantially from 57% to 46% in the period between Summer 2022 and Winter 2022-2023.

The data do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions about the influence of COVID-19 on democratic satisfaction in Europe, nor do they shed light on why Poland and Hungary had a significant drop in this level at the beginning and end of the pandemic, respectively. It could also be due to a variety of internal factors that are unrelated to the pandemic, especially because both countries have experienced a reduction in democratic attitudes prior to the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Having cleared so, the graph clearly illustrates that on a European level, there has been neither an increase nor a major decrease in democratic satisfaction.

Of course, this does not mean that the health crisis has no threats in store when it comes to endangering democracy. According to Jungkunz (2021), the COVID-19 pandemic has had and continues to have the potential to drastically reinforce the social and political polarization that has been slowly building around Europe (Kriesi et al, 2008, “West European Politics in the age of globalization”, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press) in the last decade. Through fear and uncertainty of the future, it has provided a window of opportunity for already powerful political actors to strengthen monitoring and control in exchange for protection and efficacy in the response (Amat et al. 2020:7). As a result, while faith in political authorities grows, democracy does not improve. On the opposite, it makes it weaker.

Herre (2022) employs data from “Our World in Data” to demonstrate that the world has become less democratic in recent years. Since 2016, six states have ceased to be deemed democracies and the number of liberal democracies has decreased from 44 in 2009 to 32 in 2022. Naturally, the number of democracies does not always reflect the number of people who have democratic rights, but the data conclusions are the same in this situation. Between 2016 and 2022, the number of individuals with democratic rights fell from 3.9 billion to 2.3 billion, with some governments having more worrisome ideals than others (India, Turkey, and Venezuela). In most cases, similar agents of destruction are democratically elected political leaders who remove the bulk of the restriction on their power, hence expanding it, and military leaders who exploit civilian corruption (Diamond, 2021: 257). Foa and Mounk (2016) claim that citizens in Western democracies are shifting away from democracy, becoming more sceptical about its usefulness and less hopeful it can alter anything in the political and social system. Although critics claim that it only affects American citizens (Inglehart, 2016:18), Kriesi (2020) studies that there is widespread democratic dissatisfaction, which is a combination of lack of representation, lack of responsiveness of the political system, and new demands of citizens that the latter cannot meet. According to this study, all southern European countries experience a sharp decline in economic performance, government responsiveness, and a complete collapse in democratic satisfaction(Kriesi, 2020:247). Several academics have described a “democratic recession” (Larry Diamond, 2015) or a democracy “on the defensive” (Marc Plattner, 2017). Others, at least in the West, found little evidence of democratic backsliding (Van Hauwaert S.M., Van Kessel, S. 2018).

Submit here

Could this downturn be predicted?

Diamond (2021) states that there were indicators of the downturn in democracy. For starters, it simply stopped expanding. Since 2009, the share of democracies has fallen from 61% of all states to 55% in 2021. The percentage of people living in democracies declined from 55% to 47% in the same years respectively. 2019 was the first year since the end of the Cold War in which the majority of states with a population of more than one million were not democratic, as well as the first year in which the majority of people did not live in a democracy (Diamond, 2021:25).

According to the EIU report on democracy, following the pandemic, the average worldwide democratic index stalled or deteriorated, even when the world rebounded to the pre-pandemic levels. Western Europe was the only region to return to those levels.

Values speak, but maybe not loudly enough. Even though some regimes gradually abandon democratic norms over time, (like Turkey), others give too little notice before a democratic shock. It would be the case of Russia and its invasion of Ukraine, where the breach of Ukraine’s sovereignty certainly sent shockwaves around the world in 2022. States members of the EU were required to meet democratic requirements upon accession, but there also has been a regression in democratic standards over time such as in Hungary and Poland.

Finally, perhaps some data-driven predictions are helpful, much as recognising the early phases of authoritarian tendencies is. However, to preserve democracy and democratic values around the world it is the citizens that play a pivotal part in recognising the dangers of not living in a democratic state and in identifying the first signals of democratic downturn before it is too late.

Be First to Comment